Mapping the Birth of a New Genre

I like maps. Is that too basic a way to start? Maybe, but it’s true. I’ve created my own maps in the past, using Google Maps — favorite restaurants in my neighborhood in Jersey City, the route I took and the stops I made while traveling by air through South Sudan, and a few small projects for freelance jobs. So I was excited to work with Neatline, which I understood to be Google Maps on steroids, or whatever performance enhancing drugs academics take.

I immediately knew that I wanted to do something with the Instagram photo/essays that I’ve been all but obsessing over, but, initially, I ran into a problem. I was primarily following the work of Jeff Sharlet on Instagram, and his project began very local. The first few photos in his series take place in the same Dunkin Donuts in a small New Hampshire/Vermont border town. Not a terribly interesting map.

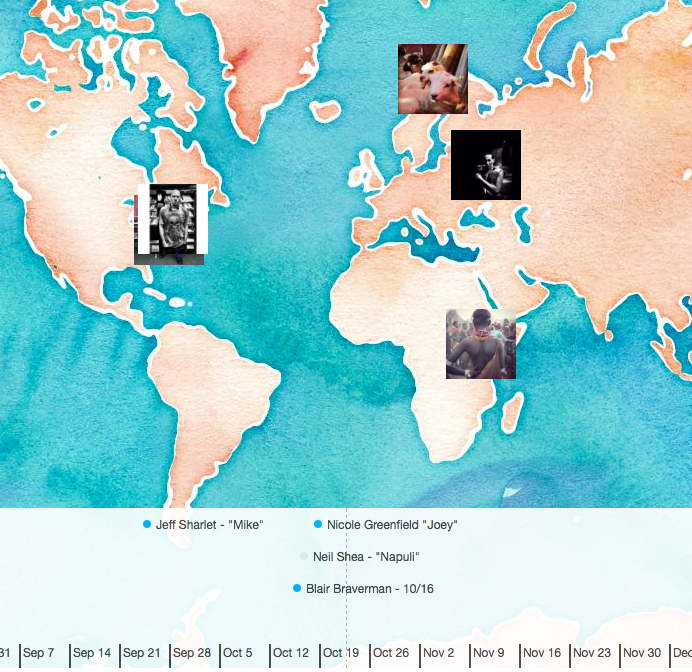

But then, a couple of exciting things happened, which broadened the scope of the project as well as landed a few more points on the map. That is, other writers started trying out the genre that Sharlet seemed to have pioneered. A few pieces popped up by writers in Brooklyn, NY, and a few more in Norway. Then, perhaps upon seeing the appeal of posting from exotic locales, Sharlet himself posted photos from a recent trip to Russia, where he was reporting for GQ. And, finally, in an email conversation with Sharlet, he pointed me to the work of Neil Shea, National Geographic photographer who, Sharlet told me, had been posting photo/essays to Instagram for weeks ahead of Sharlet.

Suddenly, it seemed like I was looking at an international movement, which seemed tailor-made for Neatline. I would have data points to add to both the map and the timeline, and in this way, I could visualize the birth of a new genre.

This was the impetus that got me started, but then some problems set in — namely, how to preserve the all-important medium while archiving these pieces. Clearly, embedding won’t work because embedded content is still tied to its original medium. If the photographer/writer takes the post down or quits Instagram, or if Instagram goes out of business, the content goes too.

Ultimately, I decided to download the photos and copy the text from Instagram and add them to Omeka as new text records. In each record, I link to the original content, but if that content goes away, the worst that will happen is that my links will be broken. But then there is the question of copyright. It appears that Instagram allows users to retain the rights to their photos and they ask that anyone who embeds a public photo from Instagram include a link back to the original. I took this to mean that if the content creator does not want me to post their photos/text, they can ask me to take them down. To date, I have secured permission from only Jeff Sharlet.

One other issue that came up: though Instagram allows users to geolocate their photos, many do not. In these cases, the location on the map was an approximation based on context from the photographer/writer’s Instagram page or information inside the caption. If I decide to continue this project, it seems that collaboration with the photographer/writer will be necessary. For example, I mentioned to Sharlet in one of our early conversations that it would be helpful if he geotagged his photos, and was delighted to note in recent postings that he has done just that.

If this Instagram photo/essay thing does become its own genre, I think it is important to catalogue, consider, and write about it as it unfolds. And, it seems that Omeka and Neatline are the right tools for the job.

If you liked this post, consider sharing it or follow me on Twitter.