The Continuous Line: Visualizing the History of American Literary Journalism

The following is an adapted version of a work-in-progress talk that I gave at The Twelfth International Conference for Literary Journalism Studies in Halifax, Nova Scotia on May 11, 2017. Video here.

TL;DR: I built an online database of works of and about literary journalism, available at ljbib.jonathandfitzgerald.com.

In thinking about how to frame this particular work in progress that I’m presenting here today, as well as the larger work that it is a part of (namely, my dissertation), I realized that they are both responses to particular challenges. Let me explain. When I began my study of literary journalism, I arrived first, as I’m sure many others did as well, at Norman Sims’ seminal book True Stories. In lieu of a master class on literary journalism, this book serves the purpose for many of us.

And I’ll never forget when I read the opening words of chapter two, in which Sims writes, “Tracing the history of literary journalism backward from the twentieth century into the 1800s, I find that it vanishes into a maze of local publications” (43). And, on the next page, he continues, “Looking for literary journalism in the nineteenth century seems daunting” (44). In the margin of my copy of the book, next to the opening lines of chapter two, I wrote “this is a challenge.” And it was a challenge I intended to take up.

“Tracing the history of literary journalism backward from the twentieth century into the 1800s, I find that it vanishes into a maze of local publications…Looking for literary journalism in the nineteenth century seems daunting” (Sims 43-44).

I had recently begun work on the Viral Texts Project, a digital research initiative led by my advisor at Northeastern University, Ryan Cordell. Using machine learning techniques, we comb through nineteenth century newspapers in search of frequently reprinted texts; texts that, in the modern parlance, went viral. So, when I read Sims’ observation that the roots of literary journalism vanish into “a maze of local publications,” I thought, I have access to those publications, and I wanted to find those roots. This first challenge formed the basis of my dissertation project, which I’ll discuss in more depth later.

The second challenge came in the form of an observation by another pillar of literary journalism studies, Thomas Connery. In the preface to A Sourcebook of American Literary Journalism, Connery conceptualizes the history of literary journalism through a series of distinct periods, and he insists, “the line from the nineteenth through the twentieth century is continuous” (xiii). As I began to consider the history of literary journalism, I wondered if this continuous line truly exists, and further, whether I could visualize it. And that impulse is what ignited the spark that led to the particular project I’m presenting today.

“…the line from the nineteenth through the twentieth century is continuous” (Connery xiii).

In part as a way to procrastinate writing my comprehensive exam paper about the history of literary journalism, I decided to try to see if I could visualize that history using methods derived from the digital humanities. I call this productive procrastination. In order to make the distinct periods of literary journalism as well as the continuous line visible, I created a data visualization based on a comprehensive bibliography of the genre, which I am compiling by mining and combining already extant bibliographies, as well as adding to the available bibliographies.

I have derived my data from five prominent sources:

- True Stories: A Century of Literary Journalism, Norman Sims

- Literary Journalism in the Twentieth Century, Norman Sims, ed.

- “Selected Bibliography of Literary Journalism Scholarship.” Literary Journalism Studies, Miles Maguire and Roberta Maguire, Spring 2011

- “Selected Bibliography of Scholarship and Criticism Examining Literary Journalism: New Additions.” Literary Journalism Studies, Miles Maguire and Roberta Maguire, Fall 2011

- The Art of Fact: A Historical Anthology of Literary Journalism, Kevin Kerrane and Ben Yagoda

My thought here is that now, still somewhat early in the development of this field of literary journalism studies, we are in the process of canon building, so I tried to pull together prominent sources that would be recognizable and respected by scholars in the field.

I extracted the text from the above sources by finding electronic versions, and copying the OCR’d text. Then, I wrote a script in R that relied on a series of gsub functions and complex regular expressions to extract element such as author name, title of the work, and, most crucially, date of publication. For example, to get the author name from the two LJS bibliographies as well as Sims’ bibliographies, which are all in MLA format, I used the following gsub:

gsub("((^[a-zA-Z]+( [a-zA-Z])?[a-zA-Z]*)|(^[a-zA-Z\u00C0-\u017F]*)|(^[a-zA-Z]+(’[a-zA-Z])?[a-zA-Z]*)), ([A-Za-z]{1,20}|[A-Za-z]{1,20}).*","\\1",.)

There might be more elegant ways to write this, but ultimately it is an effort to account for variations in names, including apostrophes and accent marks.

To extract titles, I wrote the following:

gsub("(^.*(“(.*)\\W”.*))|(^.*?\\. ([A-Z].*?)\\. [A-Z]*.*)","\\3\\5",.)

Getting the years from the bibliograhies is a bit more straightforward:

gsub(".*(\\d{4}).*","\\1",.)

I used slightly different configurations of the above to extract data from The Art of Fact because I was working from the table of contents rather than a bibliography.

I created a dataframe that included columns for the full citation, the source of the entry, whether it is a primary or secondary source, year of publication, author last name, and author first name. I also created a unique id for each entry by combining the author’s last name and year of publication. Finally, using Lincoln Mullen’s gender package, detailed here, I determined the gender of each author. (I manually assigned gender where it was unclear from the first name or the name was abbreviated.)

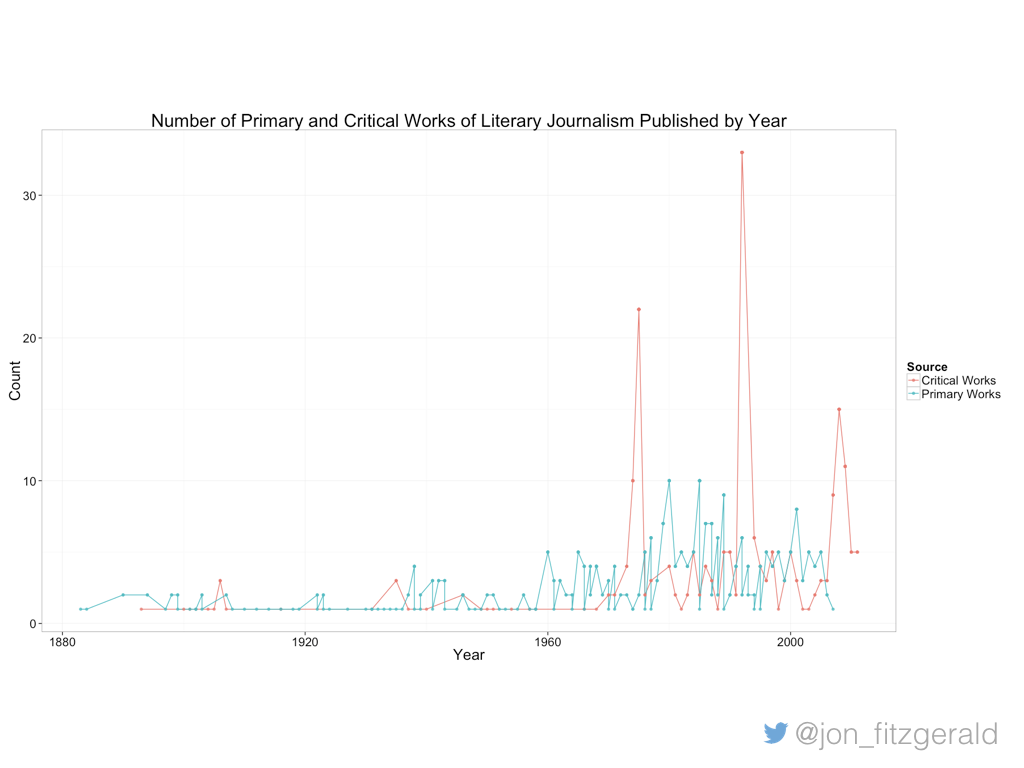

From this, I created the above visualization, showing the number of works published by year, and separated by primary or secondary source. In short, I had, in the most literal sense, created Connery’s continuous line. We’ll return to this visualization in more detail in a bit.

But it occurred to me, after I created this initial visualization and got on with the work of writing, first my exam papers and now my dissertation, that even more valuable, perhaps, than the visualization, are the data from which it is composed. That is, it occurs to me that having a database of nearly 600 publications of and about literary journalism could be helpful for me in my scholarship, as well as to other scholars.

With that notion, and in another case of “productive procrastination” I assembled this data into an searchable database, accessible online as a Shiny application at ljbib.jonathandfitzgerald.com.

There are three sections to the site: the bibliography appears on the first screen. In the second tab is the timeline visualization I previously showed, and in the final tab, I present some experimental work with gender in the corpus.

The bibliography is basically an interactive database. You can click each of the column heads to sort the table in ascending or descending order by the value of that column. You can use the search box above to search the database, and using the drop downs to the left, you can filter the information by source, author last name, and whether it is a primary or secondary source. You can also use the timeline slider to narrow your results down to a particular time period or year that you’re interested in. I find that combining these features is most valuable. You might want to view, for example, all primary works of literary journalism published in the 1930s. If you do so, you’ll get 18 results from George Ade to George Orwell.

The next tab shows the visualization I presented before, that continuous line of literary journalism, but it is interactive. So, for example, you can filter the view to show only primary or secondary sources, and, again, you can narrow by year. Thanks to the plotly package in R, you can also hover your mouse over any of the points on the graph to see year, count, and type information.

From this visualization, you can see, particularly if you filter to view only the primary sources, the distinct periods or waves of literary journalism that Connery and Sims and others talk about. There are peaks around the turn of the century, in the late 1930s and early 40s, again in the 60s and 70s (the new journalism), and finally in the 80s (the new new journalism). I should note that the latest citation from the bibliographies is from 2011, which is why the line appears to drop off after that.

Finally, the third tab is, at present, the most experimental feature, and one that is highly relevant to my larger work in progress, my dissertation. In accepting Norman Sims’ challenge to trace the history of literary journalism back into the nineteenth century, I came across a lot of writing, particularly by women writers and often in a kind of sentimental style popular at the time, that strike me as early examples of the genre we would come to call literary journalism. There’s just a couple of problems, most histories of the genre trace its roots back to the emergence of realism, not its precursor sentimentalism, and most histories and bibliographies, as we can see here, lean heavily toward male authors.

So, I offer a visualization that counts the number of publications per year, but segments them by gender. Again, you can filter by gender or by year, and you can also separate the graphs to see them stacked as opposed to combined. The first thing you’ll notice is that male authors far outnumber the women authors that are listed in extant bibliographies.

For example, in 1992, the year with the most publications, 38 were written by men, while 10 were written by women. And, as the bar graph makes clear, this pattern is seen across the timeline. But, as a person interested in the nineteenth century roots of the genre, what is even more striking is that from all of the source I’ve pulled together, the earliest publication by a woman is in 1936 (it’s Martha Gelhorn’s The Trouble I’ve Seen). Now, certainly, far fewer women than men were writing in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, but where is Margaret Fuller, or Nellie Bly, or Fanny Fern, or Nell Nelson, just to name a few?

I know that there has been work in recent years to correct this imbalance, including the spring 2015 special issue of Literary Journalism Studies, but as we continue in this crucial canon-building stage of the field’s development, I hope more of us will turn our attention to rectifying this situation. This is my third motivating challenge.

For my part, my dissertation, which I’ve titled “Setting the Record Straight: Women Literary Journalists Writing Against the Mainstream,” seeks to restore some of these women writers from the nineteenth century to our collective memories, and then to show how their legacy persists throughout the genre’s history. I will certainly be adding my own bibliography to this site.

And, in that spirit, I want to end by asking you not only to feel free to use the site, and, as it is in Beta, to use the email or Twitter link to tell me about any problems you find—technical or scholarly—but also to contribute your own sources as well. Whether you feel like there’s a particular author or source that should be added, or if you have an entire bibliography or database that could be included, email me; I’m eager to add more data here and make this an even more valuable resource to scholars in the field.

To summarize, this work in progress was ignited by the possibility that I might track down the roots of literary journalism from Sims’ “maze of local publications.” It was pushed along by the ability to visualize the breadth of the genre’s history through the lens of Connery’s “continuous line,” and it is now fueled by a desire to overcome the third challenge, the lack of women writers in our canon.

And, as for this particular project, I hope that this proves to be a useful tool, but even more than that, I hope that the visualizations on offer and those I will be adding in the future might help us to see our field in new ways, to identify that gaps where they exist in our growing canon, and to further and better theorize the 200-year history of literary journalism.

And, just for fun, here’s a word cloud derived from the titles in the combined bibliography:

If you liked this post, consider sharing it or follow me on Twitter.