What Made the Front Page in the 19th Century?: Computationally Classifying Genre in 'Viral Texts'

The following is a lightly revised version of the text of a talk I gave at the 2016 Keystone Digital Humanities Conference, held at the University of Pittsburgh. I’m grateful to have had the opportunity to present and for the helpful feedback I received there.

I’m happy to be with you today on behalf of the Viral Texts Project, a project of the NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks at Northeastern University. The Viral Texts Project was initiated by Professors Ryan Cordell and David Smith as a way to computationally discover reprinted texts in nineteenth century newspapers.In the nineteenth century, due to lax or non-existent copyright laws, it was very common for newspaper editors to reprint content from other papers, sometimes with slight attribution, but often with no acknowledgment at all. In an effort to identify these viral texts, the team created “algorithms for detecting clusters of reused passages embedded within longer documents in large collections” (Smith et al.). This work is described in previous articles, available from the project’s website, and is not my focus here, but the data that I work with is the direct output of these efforts to identify reprints.

The project was quite successful at identifying reprints—millions of them, in fact—but this led to a new challenge: sorting through those millions of reprints in a meaningful way. A significant goal early on in the genesis of the Viral Texts Project was an effort to create a searchable online archive of reprinted texts that would provide an entry point to the dense corpora of nineteenth century newspapers and allow other scholars to conduct research.

In a recent article in American Literary History, Cordell identifies the challenge: “When every nineteenth-century newspaper brims with original and reprinted content of all kinds, it is difficult to know where to even begin studying that content” (Cordell). Clustering the texts into groups of reprints is one way to begin, another is to group those texts by genre.

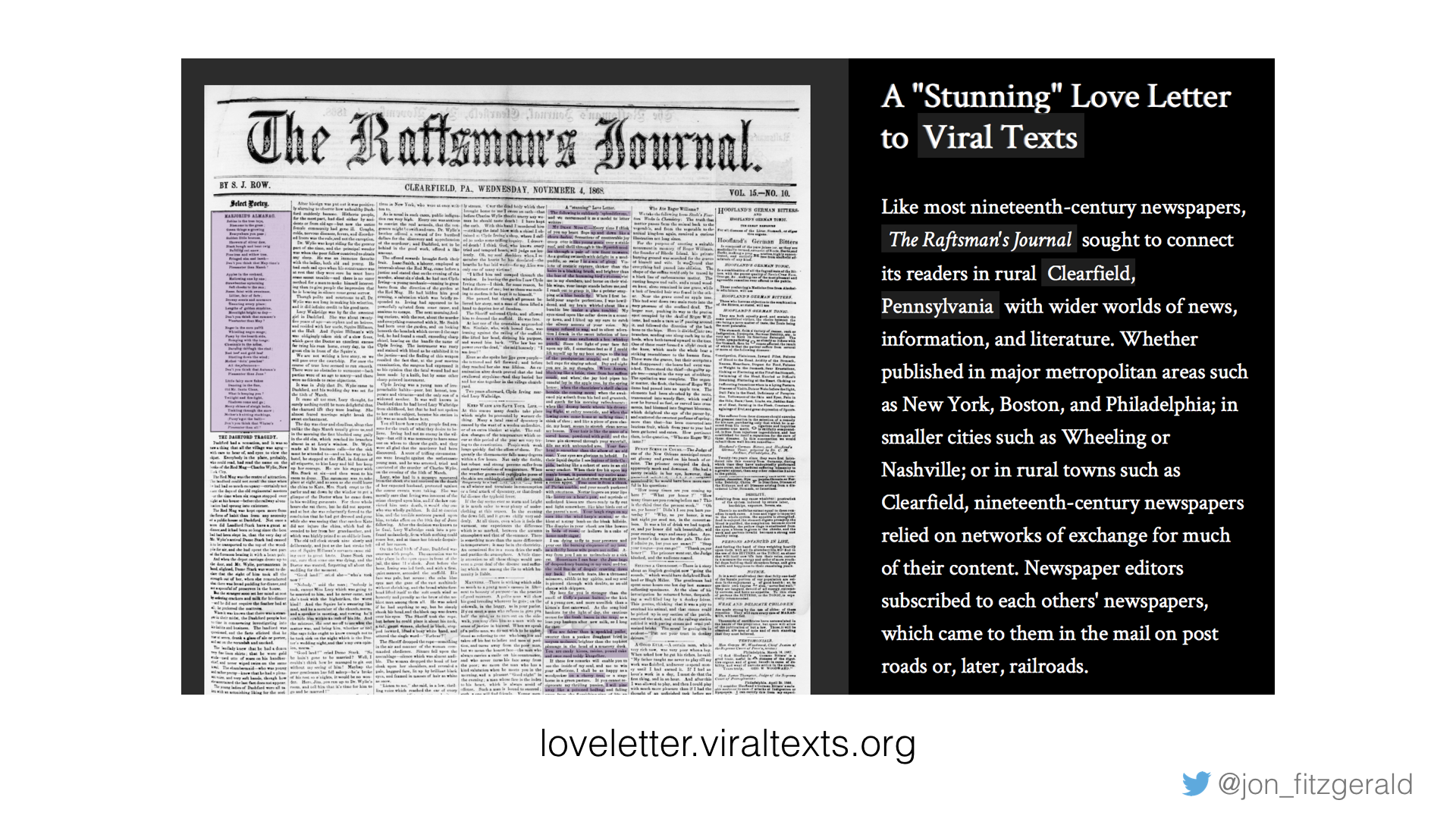

Easier said than done. I’m not sure if you’ve ever seen a nineteenth century newspaper, so I wanted to show you one.

As a way to make our texts apparent and to visualize our findings on virality, my colleagues and I created a Neatline exhibit, which we called “A Stunning Love Letter to Viral Texts.” We annotated a page of The Raftsman’s Journal, a regional paper out of Clearfield, Pennsylvania. We chose this particular paper and this particular issue because it is representative of many nineteenth century newspapers, and also because it contains one of our favorite reprinted texts, here titled “A Stunning Love Letter.” This is online at loveletter.viraltexts.org and I’ll invite you to explore it, and if nothing else, to read “Love Letter,” because it’s incredible. But I want to show you this to give you a sense both of what a typical nineteenth century newspaper looks like, and also to illustrate just how viral many of these texts could go.

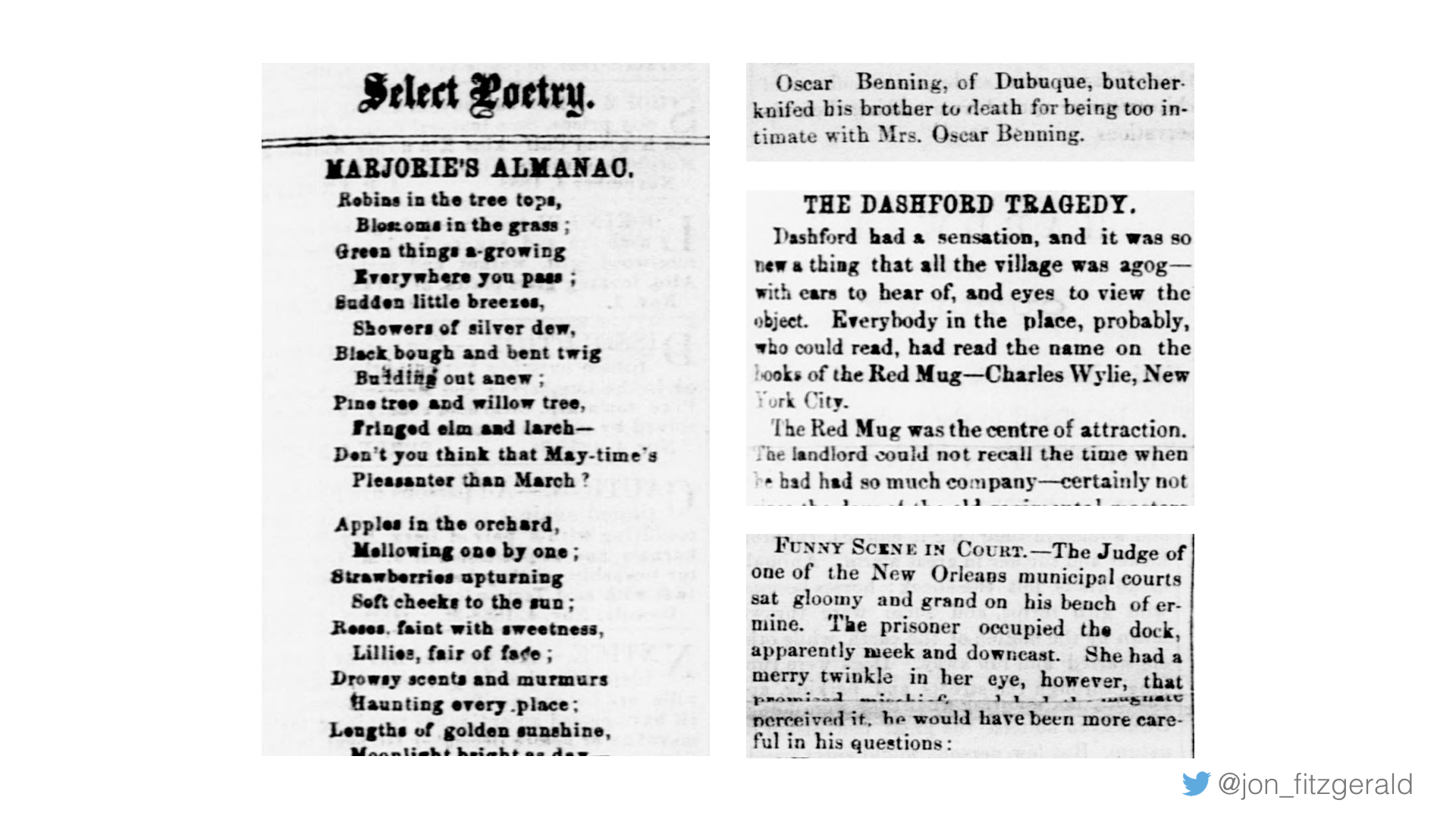

Just about every item you see on this page is a reprint. And take a look at the genres represented—we have poetry, news, fiction, vignettes, lists, jokes, among others. Likewise, the topics represented here are broad; there are pieces about scientific discoveries, etiquette, parenting, religion, and medicine. And, there’s an advertisement.

Suffice it to say that any researcher interested in determining just what made the front page in the nineteenth century, as my talk is titled, would have a difficult time knowing where to start. This broad array of genre and topics, however, also illustrates the challenges related to classifying these texts in a meaningful way. On the page of a newspaper and to a human reader, those genres seem obvious, but how can we map those human understandings of textual difference across millions of clusters? What happens when machine models can’t match human models? These questions and associated challenges, the ways I attempted to overcome them, and how I learned that overcoming the challenges might not be the point at all, will make up the bulk of my talk today.

As you’re undoubtedly aware, genre is an incredibly fluid concept. As Christof Schöch notes, “The concept of literary genre is a highly complex one: not only are different genres frequently defined on several, but not necessarily the same levels of description, but consideration of genres as cognitive, social, or scholarly constructs with a rich history further complicate the matter” (1).

Or, more concisely, according to Ted Underwood, “Centuries of literary scholarship have failed to produce human consensus about genre” (“Understanding Genre” 7). Both Schöch and Underwood are referring to literary genres, and if the ambiguity of genres is a challenge when it comes to differentiating between poetry, prose, and drama and their attendant sub-genres, it is all the more difficult when looking at the broad array represented in nineteenth century newspapers.

As Underwood points out, computers trained by humans to identify genre will be confounded in the same way that human readers are: Underwood writes of his own project to identify genres in texts from the HathiTrust, “The model was trained, after all, on examples tagged by human beings; the whole point of doing that was to reproduce as much as possible the contours of the boundary that separates genres for us” (“Distant Reading”).

My methodology draws on the efforts of several other researchers who, in recent years particularly, have taken up the challenge of using computational methods to identify literary genres. Among these are Jonathan Hope and Michael Witmore who worked with genre in Shakespeare’s plays, Lena Hettinger and colleagues, who tested a variety of computational methods to identify genres in German novels, and most significantly, Ted Underwood who, as I noted, has been working with texts from the HathiTrust.

In my own attempts, I have certainly learned from their efforts, and also very self-consciously tried to infuse my work with the exploratory emphasis that is baked into the work of the Viral Texts Project. That is, as the project developed, my objectives have grown to include not just the creation of an effective classifying method, but also to come to a better understanding of how genres operated in nineteenth century newspapers. I quickly came to understand that I had at my disposal a unique corpus and a means to read that corpus both from a distance and up close. To realize both of these goals, I have been working with Professor Benjamin Schmidt from Northeastern’s history department to develop a classification method that is suitable to the Viral Texts corpus. The method we’re working on uses topics derived from topic modeling a corpus to train a classifier.

In a blog post in which he details his experiments with this method on a corpus of 44,000 television episodes, Schmidt acknowledges Underwood’s work and explains his reason for using topics as opposed to words as features. Schmidt writes, “To reduce dimensionality into the model, we have been thinking of using a topic model as the classifiers instead of the tokens. The idea is that classifiers with more than several dozen variables tend to get finicky and hard to interpret, and with more than a few hundred become completely unmanageable.” So there are practical reasons for seeding a classifier with topics as opposed to words or other features, but, again, I chose to work with this method for the ways in which it could serve my exploratory purposes as well. Combining topic modeling and classifying opens up the corpus in a variety of promising ways.

The first step in creating a classifier to identify genres is to manually assign genres to a selection of texts. That is, I randomly selected 500 clusters from the Viral Texts data, read them, and made decisions regarding their genres. For my first attempt at this, I collaborated with and was guided by Ryan Cordell. Then, after a tremendous update to our database with the inclusion of newspapers from Gale (UK and US), Trove, and APS, in addition to Chronicling America, which is what we started with, I created a new set of hand-tagged genres. After reading over 1,000 clusters, it became clear that the task of assigning genres to the wide array of reprinted material would prove challenging. Poetry, Advertisements, and News were natural choices, but I was left with the question of the various other prose genres that are represented in our corpus. Ideally, I could separate these out into smaller constituents like vignette, sketch, opinion, and advice, but it turns out that the subtle differences between these genres proved confounding for my classifier, as they often do for human readers as well. Ultimately, I settled on four top-level genres: poetry, news, advertisements, and prose. For each of the clusters tagged prose, I also assigned secondary genres relating both to content and form. I intend to revisit these secondary genres later in an effort to train a classifier to identify distinct genres from among the prose corpus.

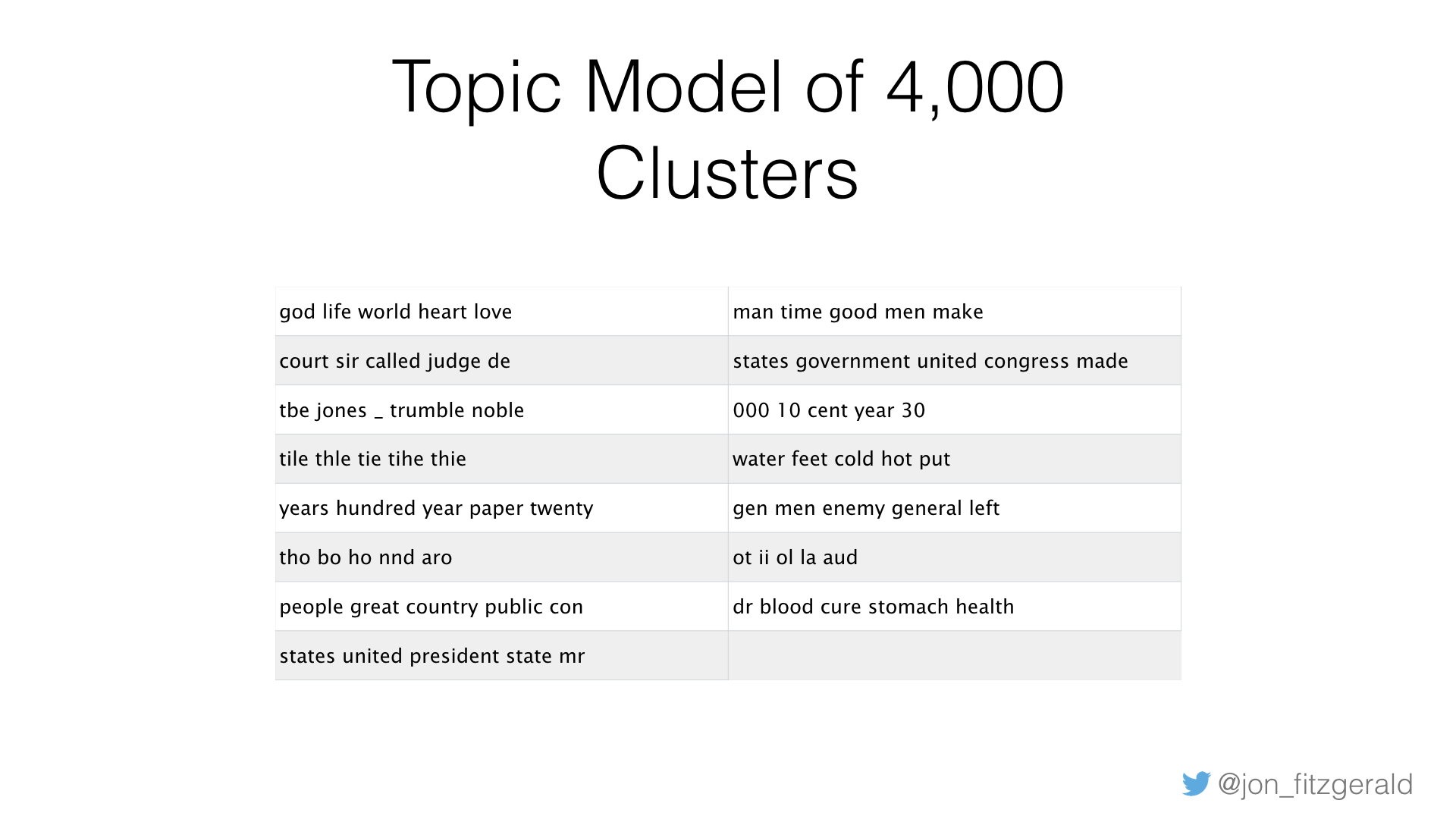

While I hand-tagged 500 clusters, in order to get a more accurate training set, I selected 50 clusters of each genre and reintegrated them into a larger corpus of around 4,000 clusters. This is a small fraction of our entire corpus, which at this point reaches to over a million clusters, but enough to test the classifier without overwhelming my computer. Using the “Mallet” package in R, I topic modeled the clusters, removing stop words. I experimented with the number of topics to generate, ranging from 5 to 500, but ultimately found that a relatively low number—around 10 or 20, and recently 12 seems to be a magic number—worked best.

Here is the output of one topic model. You can almost guess the genre by looking at the topic names, but you’ll also notice some bad OCR was picked up as well.

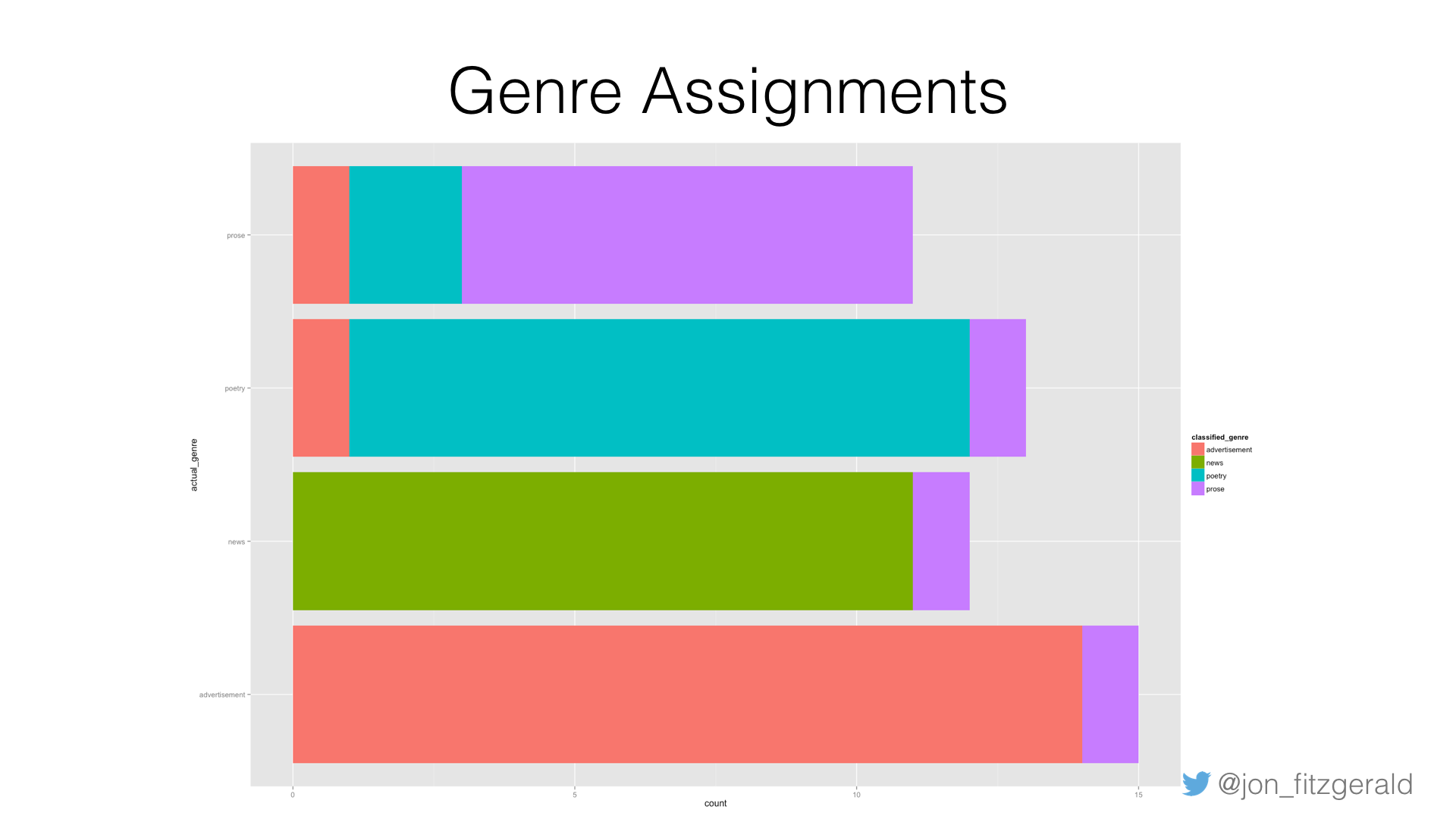

I created a matrix of the topics and the probabilities and selected a training set randomly from the matrix. Next, I trained a model using logistic regression and applied the model to each of the four genres. As noted above, one of the benefits of using computational methods for classifying genres is that the results are rendered in terms of probabilities. That is, the output of the classifier indicates the probability that a text belongs to a genre. We can select the genre with the highest probability as a kind of best guess, but it is also useful to see the other probabilities. For now, however, by selecting the best guess I can visualize how the model performed for each genre in the test set.

Here is a histogram where the actual genre appears on the Y-axis and the number of clusters assigned to each genre is on the X-axis. The bar is colored to indicate the genre each cluster was assigned by the classifier. You can see that the prose genre, colored purple here, is slightly problematic; it has the lowest accuracy at around 63% and shows up as miscategorized in each of the other genres. Ads and news items are both mistaken for prose. In this case, some poems were misclassified as ads and prose, and the prose genre itself was mistaken for poetry and advertisements. While this was a particularly good result, with an accuracy of 86%, the results differ each time the classifier is run, therefore, to get a sense of the overall accuracy, I run the classifier a number of times and average the results. Typically, after running the classifier 20 times consecutively, I arrive at somewhere between 75-85% overall accuracy.

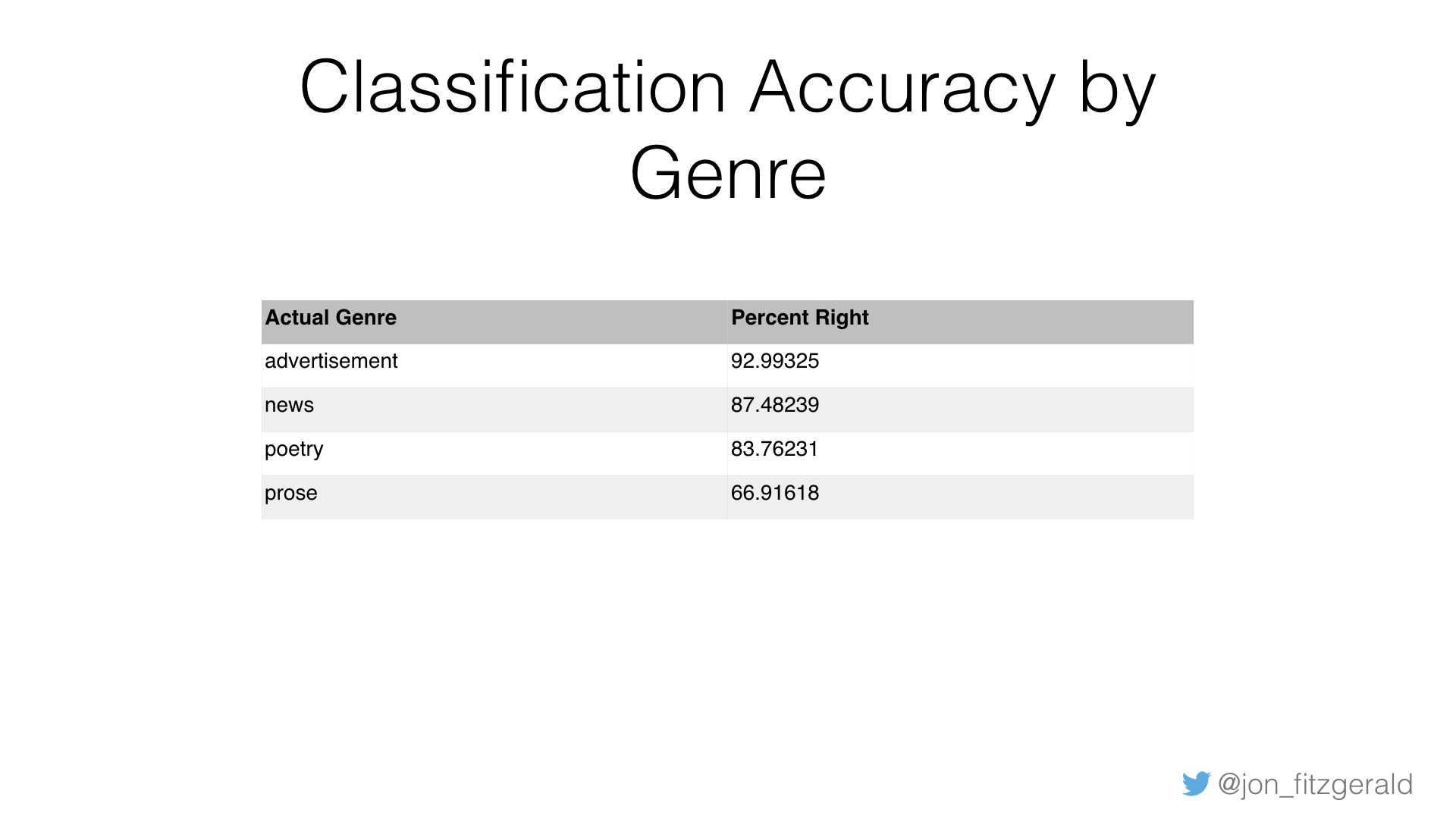

As this table illustrates, advertisements, poetry, and news are much more accurately classified than prose, but this is owing to the fact that, again, as a combined genre, prose is, at this point, really a kind of “everything else” category.

I can then apply the model to unknown clusters. I label all clusters without hand-tagged genres as “unknown” and create a data frame that includes just those clusters. I then run the model on that data. The result is every unknown cluster is assigned a genre. I create an additional output that shows me not just the best guess for each cluster, but all of the other guesses as well, arranged in order of probability.

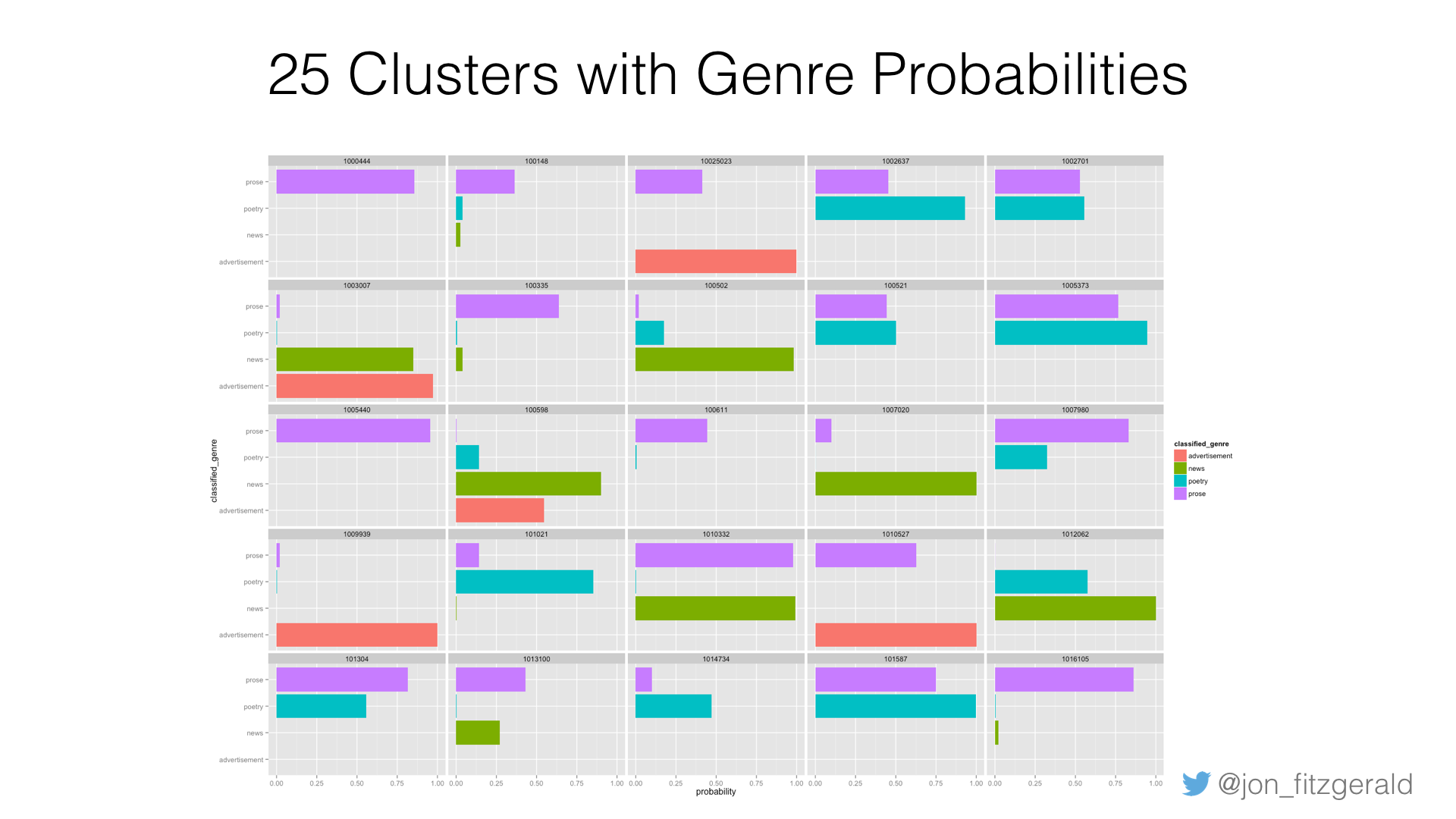

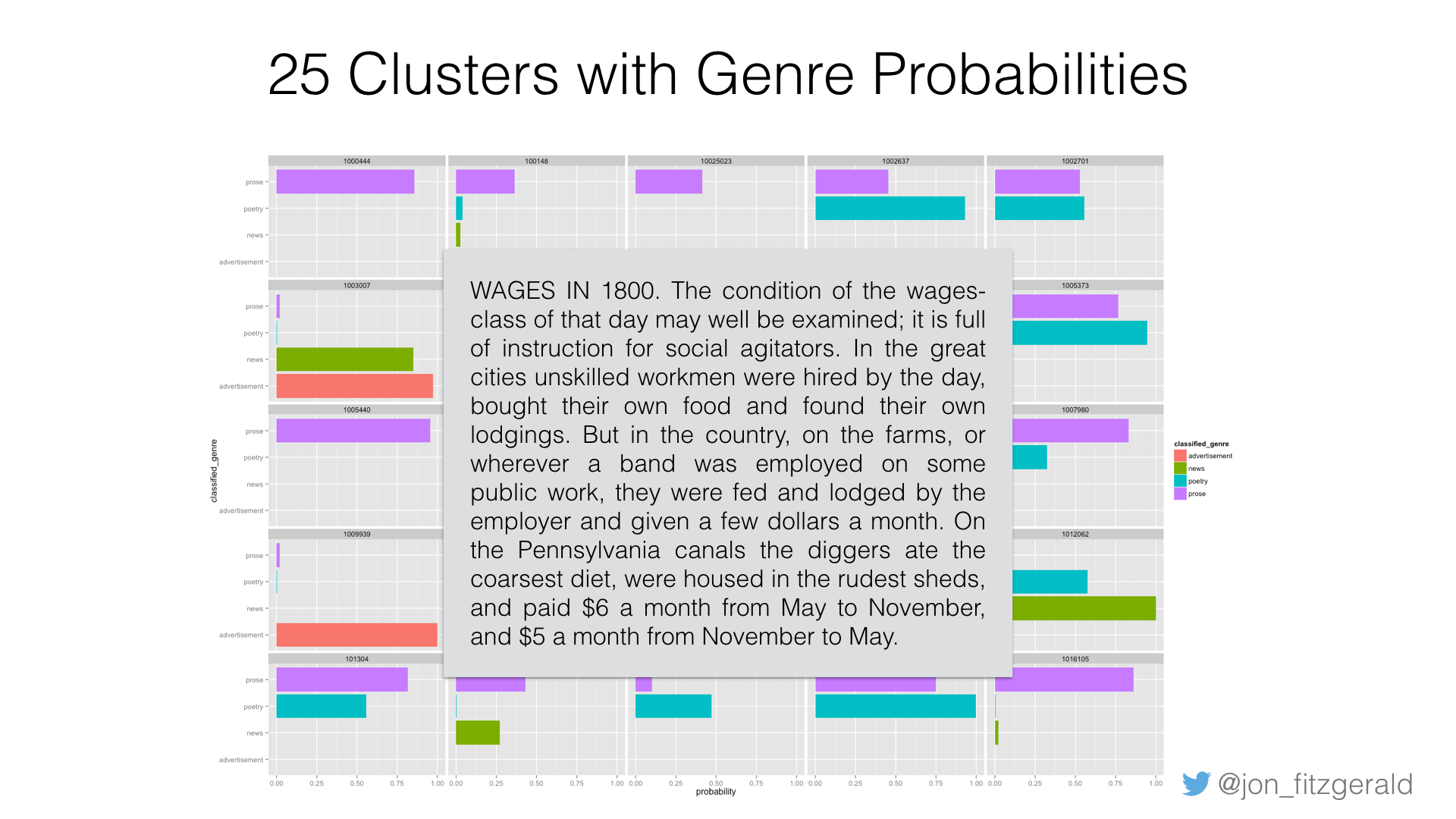

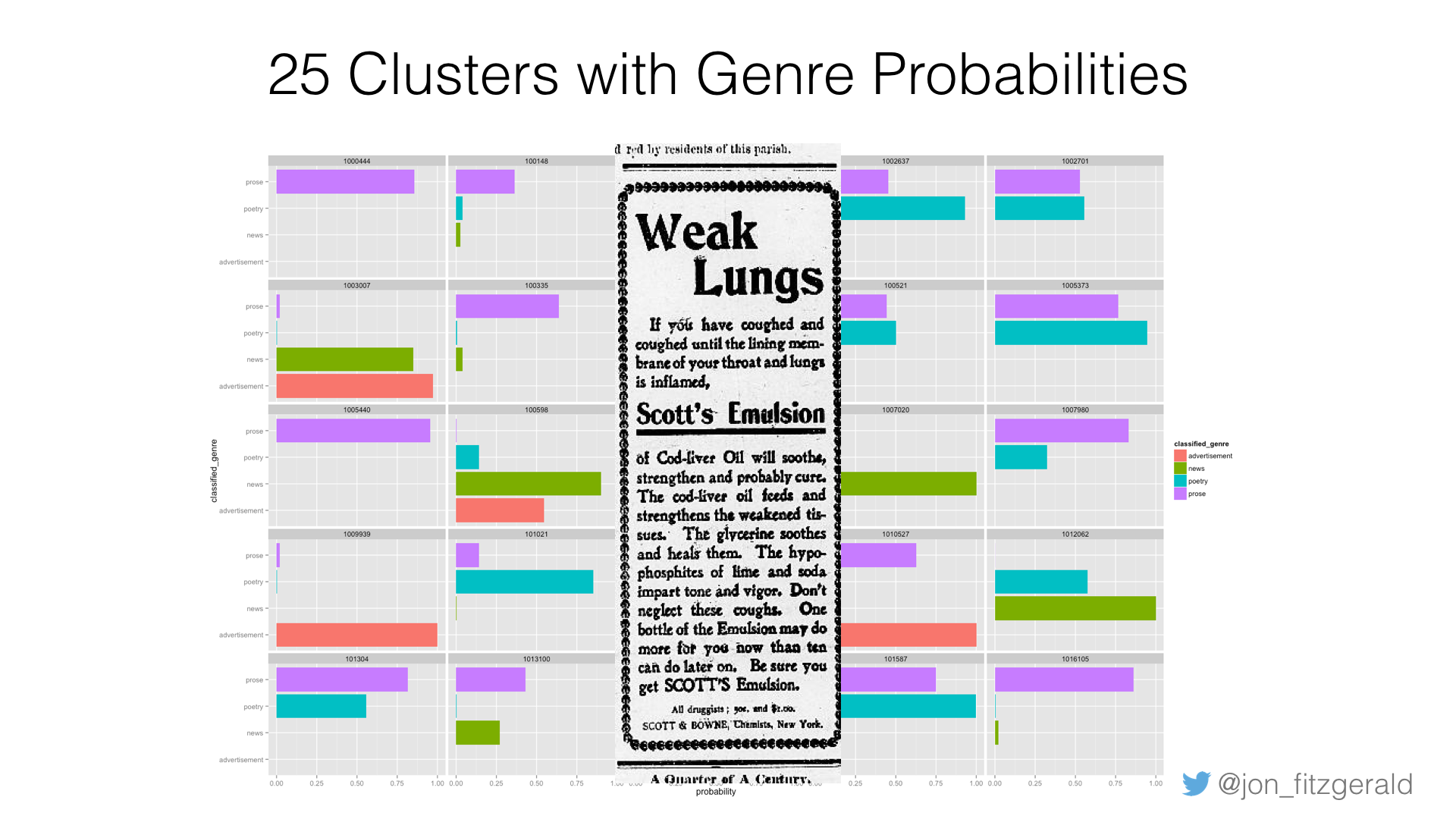

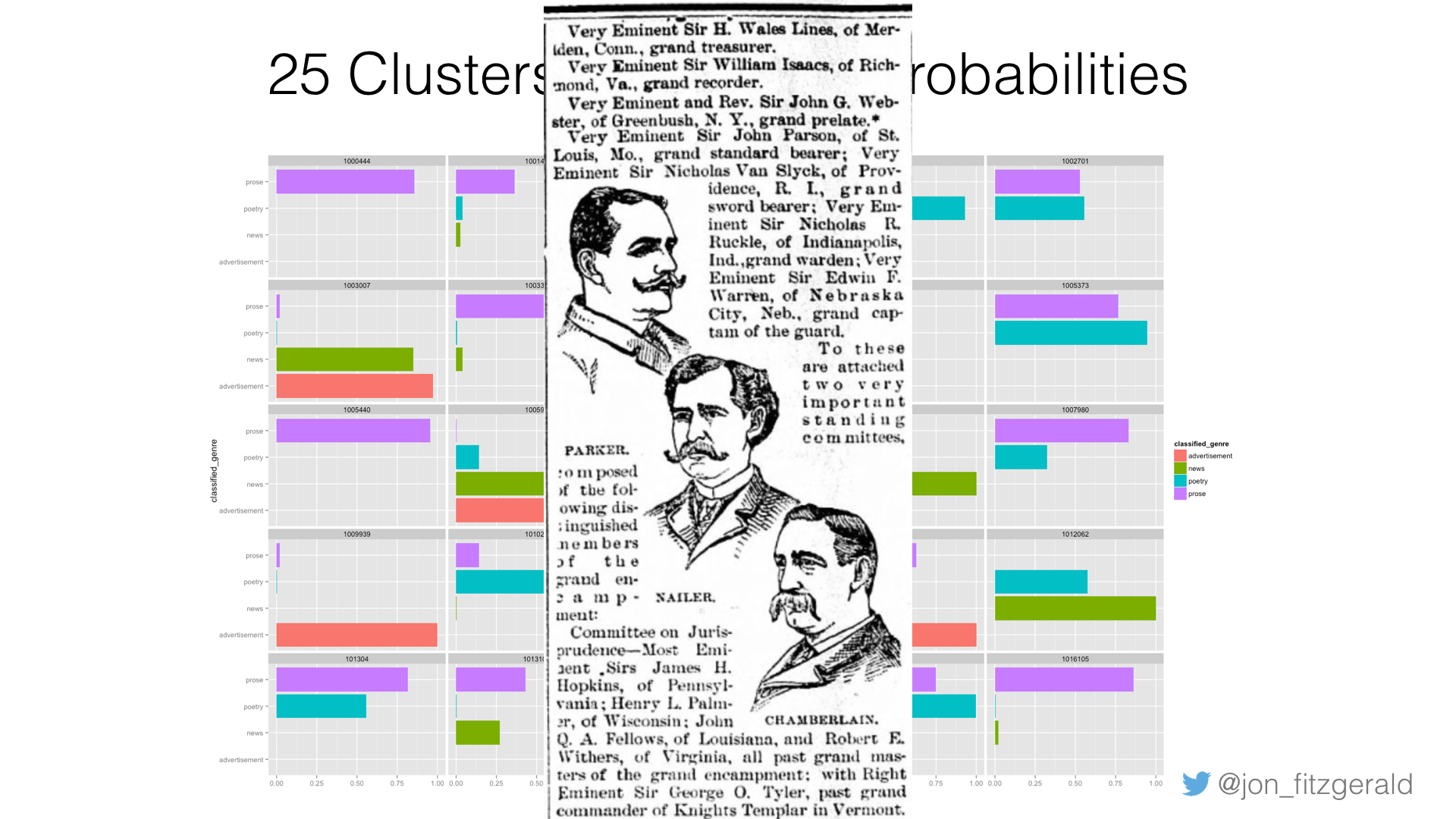

Here’s a visualization showing 25 formerly unknown clusters, the genres they were assigned, and the probability that they belong to each genre. In most cases, the decision is split between two genres, and in a couple cases only one genre is shown meaning that the probability that the cluster belonged to any other genre is too low to be relevant.

Let’s look at cluster 1010332, which you can see is split just about evenly between prose and news. It turns out this is a historical piece about wages in the 1800s, which appeared in 1885. It notes that “on the Pennsylvania canals, the diggers ate the coarsest diet, were housed in the rudest sheds, and paid $6 month from May to November and $5 a month from November to May.”

Or check out 1009939, which is classified almost completely as an advertisement. Sure enough. It reads, “If you have coughed and coughed until the lining membrane of your throat and lungs is inflamed, Scott’s Emulsion of Cod-liver Oil will soothe, strengthen and probably cure.” Not very reassuring.

Finally, let’s look at 1012062, which is mostly identified as news, but also poetry. This is part of a longer article about the Knights Templar. The piece is occasioned by the triennial conclave in Washington and occupies a full page in the September 19, 1889 issue of the Jamestown Weekly Alert. After a brief history of the knighthood, this List of officers elected in 1886 to the Grand Encampment is offered. Is it news? Poetry? You decide. But joking aside, you can see why it might be misclassified as poetry.

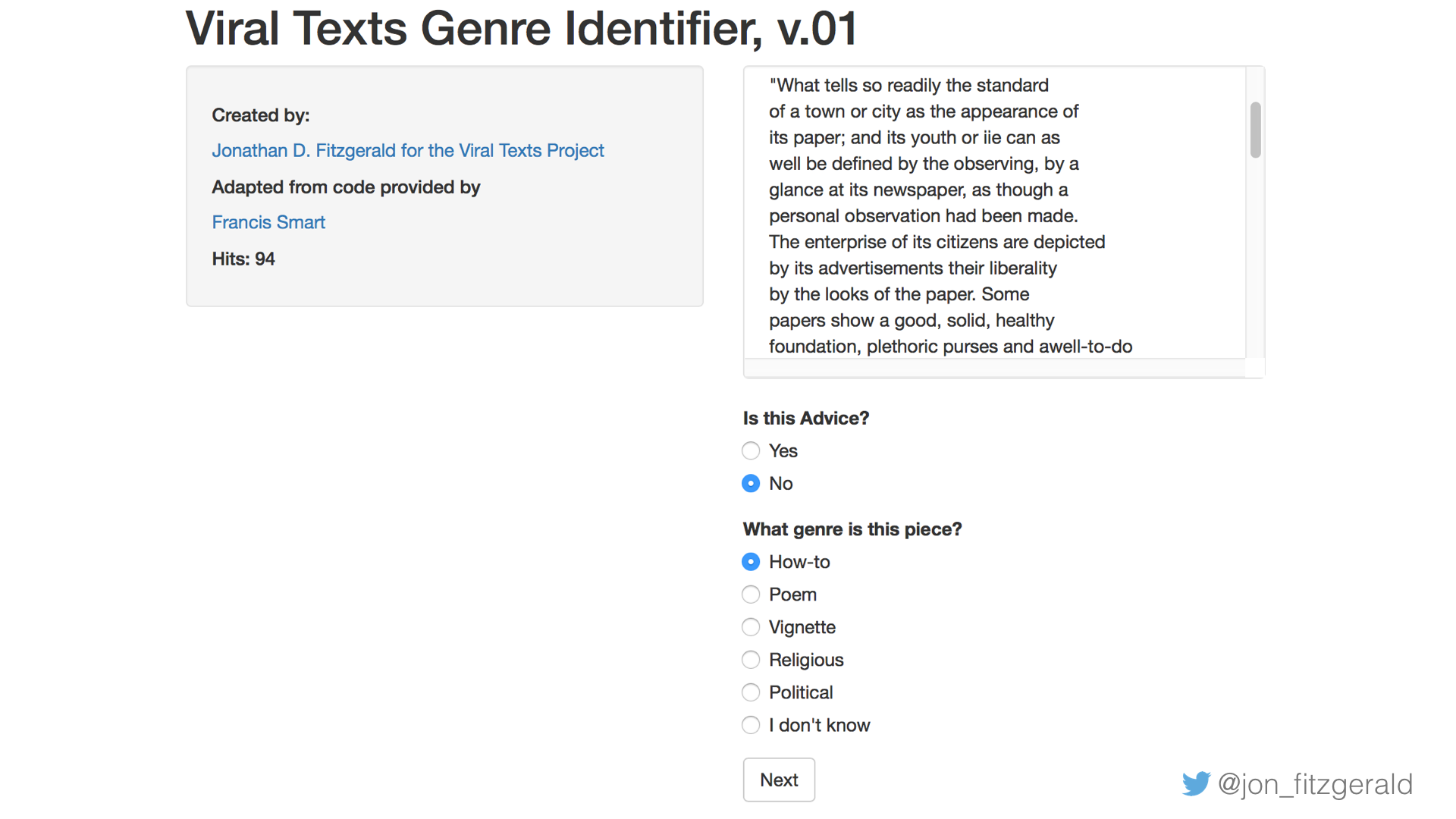

While I’m pleased with these results in the sense that they indicate that the classifier is working well, if I want this data to be useful to other researchers, I want to create a method for verifying the results. To that end, I’ve begun work on a Shiny app that will allow users to check my work. Here’s a screenshot of the work in progress.

As you can see, it serves up the text and asks the viewer if it indeed belongs to the genre it was classified as. If the user selects “No,” a list other possible genres, listed in order of probability, are presented. I hope to have this online soon.

One of the promises of a project like this is, according to Matthew Jockers, to “lead us not only to a deeper understanding of the genres…but also to clearer definitions of genre itself” (77). The more I worked with these texts and attempted to design the most accurate classifier as I could, this quote kept coming back to me.

Of course I want a classifier that performs well, as part of the purpose of this project is to make the texts more accessible to researchers who might be interested in one or another particular genre. As a researcher who studies literary journalism, however, the genres I’m most interested in—vignettes and sketches—fall under that broad category of prose that I have not been terribly successful at identifying. On the one hand, this is frustrating. I’d like to be able to click a button and bring forth every text that I might actually be interested in reading. On the other hand, it occurred to me that not only has this work has been revelatory about genres in nineteenth century newspapers, but also about the definitions of genre itself.

One of my first realizations along these lines came when it occurred to me that I was trying to squeeze newspaper writing from the nineteenth century into the mold of contemporary genres. Aside from poetry, none of the genres look like you’d expect them to look today. Early in my project, before we acquired more data from the latter half of the nineteenth century, it was difficult to even find news in these newspapers. As, I’ve discussed, the wide array of prose genres have little correlation with the kind of writing we expect to find in contemporary newspapers. Even advertisements, written often as narratives or testimonials in the nineteenth century, are unfamiliar. I came to this material with a preset notion of what I would find and until I began to let the data show me what was actually there, I was banging my head against the wall.

In light of this, my project became to better understand the kinds of writing that were popular in the era on their own terms. And then, if there is any way to carry this forward into my research on literary journalism, it is to begin to theorize how and what these genres became as the nineteenth century came to a close and the twentieth century ushered in a dramatic reshaping of the newspaper landscape in the United States. Clearly, we don’t often find poetry or vignettes or even many sketches in contemporary papers. There just wasn’t any room for this kind of writing in the new so-called objective newspaper at the turn of the century. But prose genres still exist in opinion sections, longer, more narrative reportage, and in advice columns. Further, even by the end of the nineteenth century the kind of writing that would become literary journalism moved into magazines and books where the presence of an author showcasing her subjectivity was more welcome.

The most interesting and perhaps most generative aspects of this project are not the genres that are easy to classify, but those that are hard. That prose texts are so often misclassified, and that the ambiguity between them is so great, raises a lot of interesting questions.

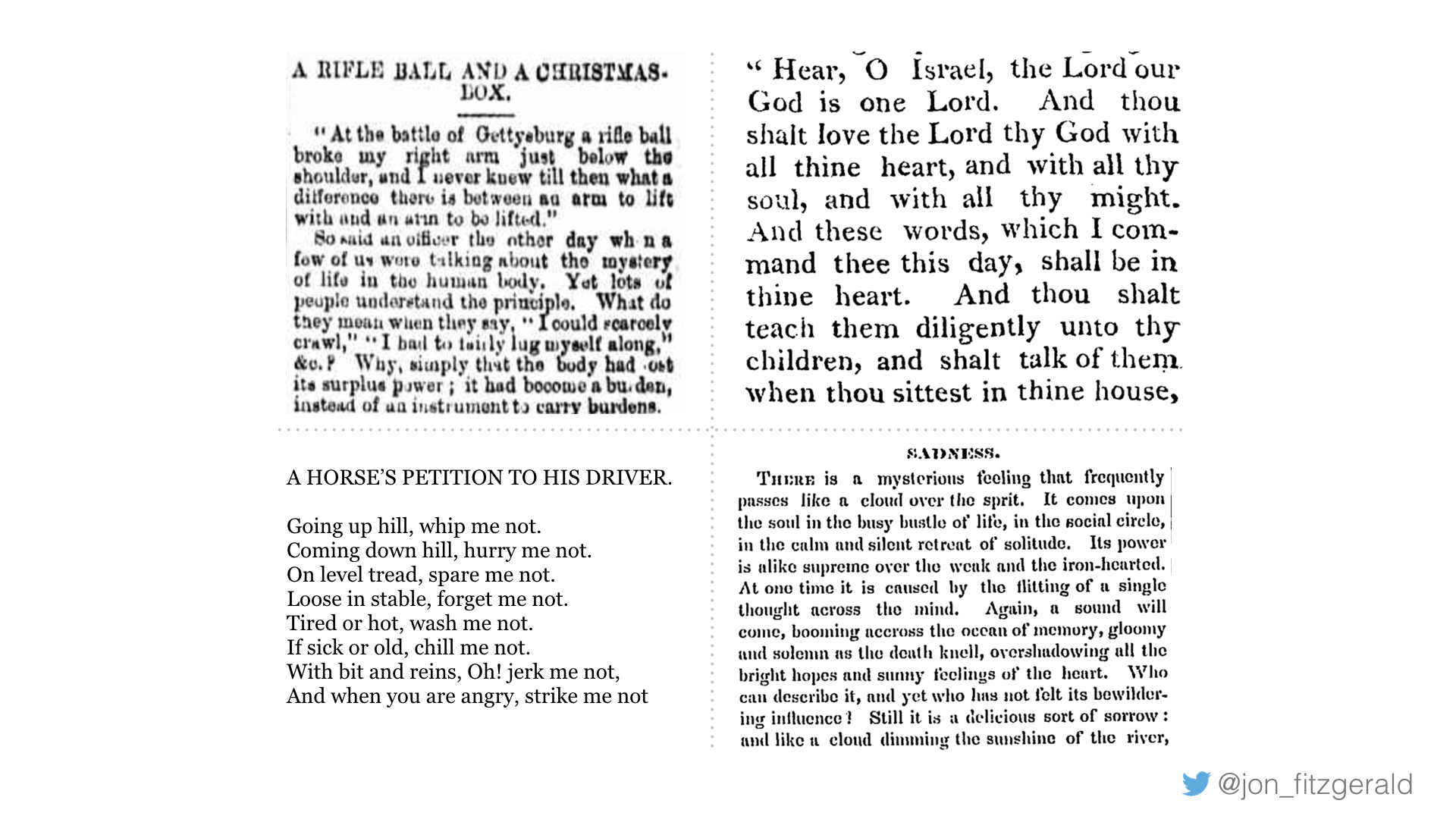

Those pieces that are clearly prose, but misclassified as poetry, for example, are fascinating because what you’re seeing is poetic language employed for expository or narrative purposes. Like the item in the lop left corner of the above image. Or poems that are more narrative in nature sometimes get misclassified as prose. The piece in the lower left-hand corner is a fun example of that. Scripture passages are often classified as poetry, which, depending on the verse, is actually quite accurate. The passage in the top right corner is an example of this. And by looking at not just the primary genre that the classifier assigned to a piece, but also its secondary genre, some really interesting pieces come forward. I’m particularly interested in those that are classified first as prose and second as poetry. Like the one in the bottom right corner, titled “Sadness.” I have so many more examples, too many to share here, but this gives you a sense of the kind of material we’re working with.

None of this generative interchange between genres was immediately clear to me when I came to the Viral Texts Project with the lofty goal of creating an accurate classifier, but the time spent reading texts and hand-tagging their genres, topic modeling them and studying the output, fine tuning a classifier, and going back and reading the results has, as all good research in the humanities should do, conjured up a new set of questions.

Paige Morgan, the Digital Humanities Librarian at the University of Miami, recently tweeted, “So much of working with data is just looking at the data,” to which I added, “and reading it.” Computational methods will continue to be helpful in considering these questions, of course, but so too will be delving into the texts and reading.

Returning to Matthew Jockers once more; in a paper he co-authored with David Mimno, they write, “The models we present here cannot represent the full meaning of individual books any more than satellite photos can show the details of individual trees. Like the satellite view, however, these macro-, or ‘distant-,’ scale perspectives on literature offer scholars a necessary context for and complement to closer readings” (768). Reading from afar and reading closely—these methods are not at odds, but complimentary and, I’d argue, necessary for this kind of work.

Works Cited

Cordell, Ryan. “Reprinting, Circulation, and the Network Author in Antebellum Newspapers.” American Literary History 27, no. 3 (September 1, 2015): 417–45. doi:10.1093/alh/ajv028.

Jockers, Matthew Lee. Macroanalysis: Digital Methods and Literary History, 2013.

Jockers, Matthew L., and David Mimno. “Significant Themes in 19th-Century Literature.” Poetics, Topic Models and the Cultural Sciences, 41, no. 6 (2013): 750–69. doi:10.1016/j.poetic.2013.08.005.

Schöch, Christoph. “Topic Modeling Genre: An Exploration of French Classical and Enlightenment Drama.” Digital Humanities Quarterly, forthcoming.

Smith, David A., Ryan Cordell, Elizabeth Maddock Dillon, Nick Stramp, and John Wilkerson. “Detecting and Modeling Local Text Reuse.” In Proceedings of the 14th ACM/IEEE-CS Joint Conference on Digital Libraries, 183–92. IEEE Press, 2014. http://dl.acm.org/citation.cfm?id=2740800.

Underwood, Ted. “Distant Reading and the Blurry Edges of Genre.” The Stone and the Shell, October 22, 2014. http://tedunderwood.com/2014/10/22/distant-reading-and-the-blurry-edges-of-genre/.

———. “Understanding Genre in a Collection of a Million Volumes.” University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, December 29, 2014.

If you liked this post, consider sharing it or follow me on Twitter.