The Myth of Maps

Here’s a safe assumption: most people in the Western world believe in at least one pervasive, life-defining myth. This myth underlies our daily lives. Where we live and work, who we associate with, and how we define ourselves are shaped by this myth. I could very well be talking about religion, and certainly life in the United States is predicated on certain religious beliefs, but there are those who deny those beliefs and actively work against them. The myth I’m describing, dare I say, is even bigger than religion, and not as easily denied. I’m talking about the myth of maps.

A paradigm shift occurred in the early modern period with regards to maps. In his essay “Cartography and the Renaissance: Continuity and Change,” David Woodward described it thusly, “by creating maps people saw, perhaps for the first time, that they could influence events and create worlds, that they could have the freedom to do things, rather than accept passively whatever God had ordained.” Though there had been maps long before the early modern period, they lacked the authority we recognize today. That is, until “the inclusion of a formal legend or map key that makes explicit the relationship between a sign and what it signifies,” as Woodward describes it.

Dennis Wood, in an essay titled “A Map Is an Image Proclaiming Its Objective Neutrality,” refers to this formal legend as “the mask no map goes without,” and it is meant to denote trustworthiness. We know we are looking at a map when we see these formalities, and we implicitly trust that the map is an accurate representation of real places. We accept the mask. Wood goes on to write, “Any discourse proclaiming its own trustworthiness is alienated discourse, what Roland Barthes called myth.”

So maps are the myth we all believe. But as Woodward points out, maps are created by people who, rather than simply reporting what is there, “influence and create worlds.” Maps, rather than being objective representations are subjective when they wear the mask that encourages us to believe in them. “It was with the presentational code that the map insisted on being accepted not as a discourse about the world (which would be open to discussion, or a fight) but as the world itself (about which we could do nothing, which we could only accept), this is to say, as myth,” Wood writes.

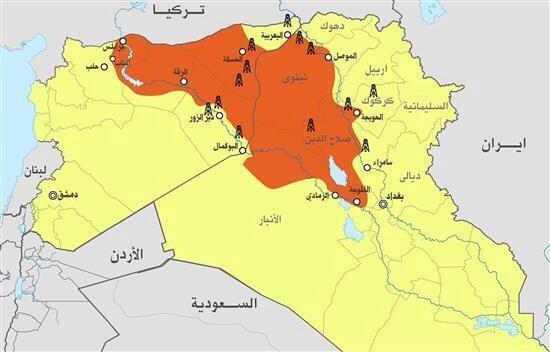

I grant that this is difficult to accept at first. Of course maps are created by people, we might say, but they are people whose interest is in truthfully representing what is. But if we consider maps a bit further, we can’t help but see the myth. See, for example, the case of ISIS, the extremist group currently — and violently — remapping the Middle East. Click over to Google maps and you will see, clearly delineated, the lines between Iraq and Syria. These are two distinct countries to you or I, but not to the so-called Islamic State in Iraq and Syria. In 2006 the group produced the following map of their plan for Iraq and Syria:

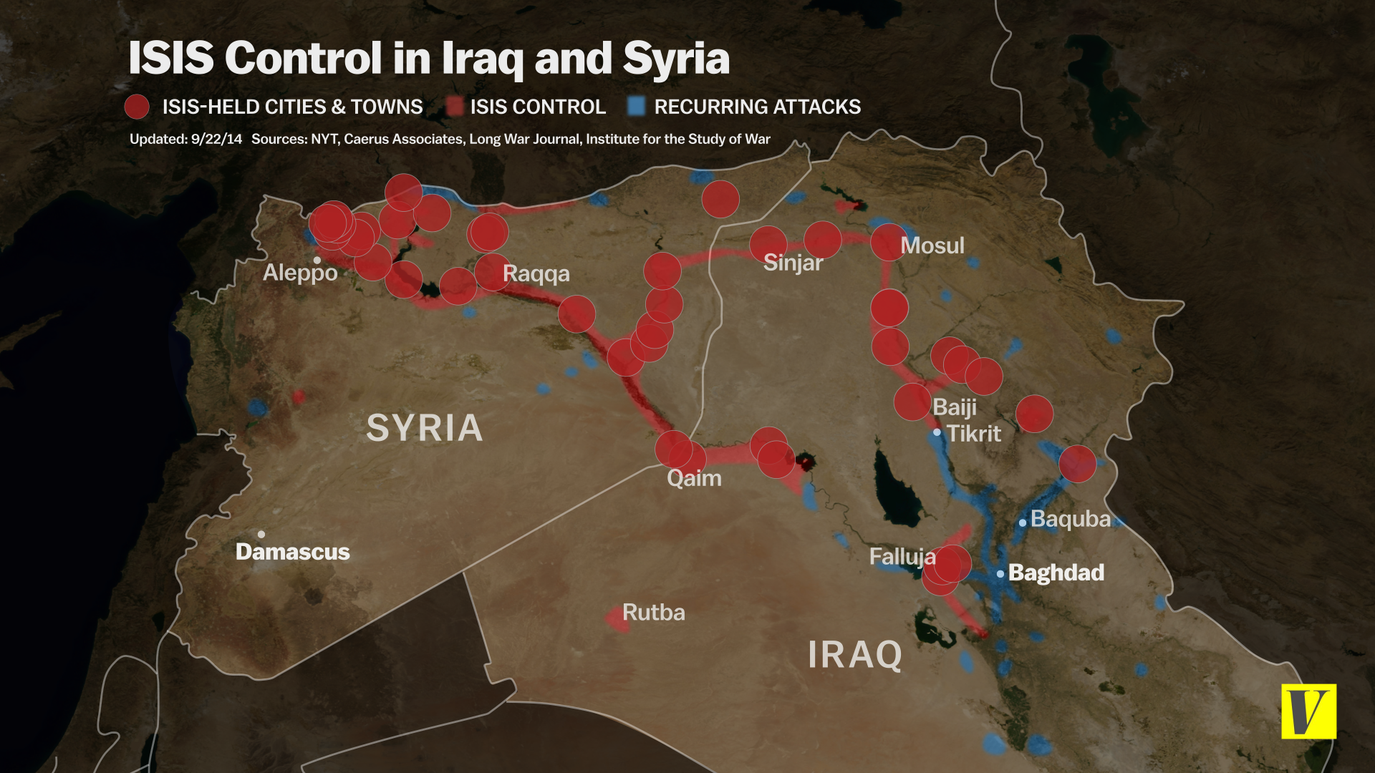

And, as of September 2014, here is what their map actually looks like:

The myth of maps is powerful, clearly. In the context of ISIS, we read a lot about the The Sykes-Picot agreement of 1916 in which the British and French arbitrarily drew lines on a map — much like King Lear dividing his kingdom based on his daughters’ performance of their love for him — of the Middle East that pretty much persists today. When I lived in Kenya, a country with something like 70 distinct ethnic groups bundled together between another set of British-made borders, the subjectiveness of the map was tangible. And, when, in 2007, shortly after I moved back home, the country erupted in ethnic fueled violence, I watched from afar with sadness but little surprise as members of those ethnic groups raged against each other.

Here in the West we are relatively clueless to the myth of maps, though the periodic redrawing of voting districts should probably awaken us from our slumber. But elsewhere, as we are (or should be) seeing, the effects of this pervasive myth are felt daily. But perhaps, even in these places, though they fight against it, the myth goes unrecognized. What is needed is a mythifying of the myth of the map.

What would it mean to “mythify” the myth of the map? As, Barthes suggests, “The best weapon against myth is perhaps to mythify it in its turn, and so to produce an artificial myth: and this reconstituted myth will in fact be a mythology.” In terms of maps, Wood writes, mythifying maps “strips the myth from the map of the world and holds it up to ask whether it is one we want to live by.”

If we force others to accept the myth of the map, it seems, eventually they will reject the myth violently. This is by no means an affirmation of the actions of ISIS, so much as a guess at what led to their violent revolt. But if we mythify the map, perhaps we can preempt this violence. I don’t know exactly what this looks like, but I know that we better figure it out — sooner, rather than later.

If you liked this post, consider sharing it or follow me on Twitter.