Re-Presenting Early Modern Pattern Poems as Material Objects

The following is excerpted from a paper I gave at Making, Unmaking, and Remaking the Early Modern Era: 1500-1800, 14th Annual EMC Conference at UCSB in February. For this project, I used 3D printers and laser cutters to re-mediate Early Modern pattern poems as physical objects. For the TL;DR version, scroll down to the bottom to see pictures.

I’m grateful for the opportunity to be here with you this weekend. I feel a bit like a fish out water — I’m not an Early Modernist. That seems like a confession that I need to make. I approached this project, rather as a Digital Humanist. I had the opportunity to study Early Modern Literature & Visual/Material Cultures with Professor Erika Boeckeler at Northeastern University, and it is was in that class that my interest in Early Modern pattern poetry and this project was born.

Prior to the late 20th century, not much critical attention had been given to Early Modern pattern poems. Dick Higgins, who is certainly one of the most foremost scholars of pattern poetry notes in his essay “Pattern Poetry as Paradigm” that the genre has not been the subject of consistent study and when it has, he writes, it “was strongly under attack by almost all critics and observers” (“Pattern Poetry as Paradigm” 401). But, despite the persistent biases against pattern poetry (or visual poetry, shaped poetry, figured poetry), Higgins, writing in the late 1980s, saw a recent uptick in attention to genre and identified several potential reasons for this surge in interest, among them, the intermedial nature of pattern poetry. Indeed, it is through this characteristic of intermediality that I enter into the study of pattern poetry here — that is, the consideration of pattern poems as objects.

There is of course a precedent for this kind of reading. Prior to the 17th century, pattern poetry was often actually inscribed on an object, thus taking its shape from the physical limitations of the object onto which the text was inscribed. But by the 17th century, pattern poetry separated from engraving on objects and moved to the page. In this rendering, Jeremy Adler writes, “the poem functions as object, a speaking artefact among other, silent objects” (141). How should this theory of poem as object inform our study of Early Modern pattern poetry? And, in what ways could we come to a better understanding of how pattern poems work (or don’t work) in light of contemporary theory and methods?

Higgins frames a potential method for answering these questions in terms of a “double semiotic,” which, he notes, as of his writing, was lacking. This double semiotic would take into account “what the pieces and their images, whether visual or verbal, for instance, meant to the times from which the pieces emerge, and some common semiotic by which we could discuss what the pieces are to us, as indicators of all aspects of their meaning” (“Pattern Poetry as Paradigm” 403).

In an effort to answer these questions, I set out to attempt to re-present several Early Modern pattern poems as objects in the most literal (and physical) sense. Using 3D printing technology, I created four poem/objects in an attempt to better understand their intermedial nature. What follows is an explanation of the theory underpinning my attempts at re-presenation, a discussion of the processes utilized, and a look at the results for three of the four poems.

Theory

There is, particularly in the Digital Humanities, an increasing emphasis on the concept of making as a way of achieving greater understanding of a historical artifact, or more specifically for our purposes, a text.

In her chapter of the “evolving anthology” Literary Studies in the Digital Age, titled “Digital Scholarly Editing,” Susan Schreibman writes, “There are, of course, many shared goals between print editions and first-generation digital editions: above all, the creation of new works by means of a re-presentation of the works of the past” (Schreibman).

In recent years, the idea of re-presenting has moved beyond creating digital versions of analog texts to include what Bethany Nowviskie calls “the fresh, full circuit of humanities computing.” That is, Nowviskie writes, “the loop from the physical to the digital to the material text and artifact again” (Nowviskie).

Process

In moving from theorizing to making, I experienced what Nowviskie — riffing off William Morris — calls “resistance in the materials” (Nowviskie). To put it another way, making 3D models of Early Modern pattern poems turned out to be a lot more difficult than I imagined. For each of the poems I chose for this project, I had a clear sense of what I wanted the physical object to look like when printed, but a far less clear notion as to how to make this vision a reality.

The software I utilized includes SketchUp, a popular and rather simplistic program formerly owned by Google and now by Trimble; MeshLab, a 3D mesh processing program; Processing, a programming language and development environment that allowed me to run a script for turning an image into a height map; and Adobe Photoshop and Illustrator in which I modified and created images of the poems. With the exception of Photoshop, and to a lesser extent, Illustrator, I had never worked with any of these programs before and the learning curve was steep.

Results

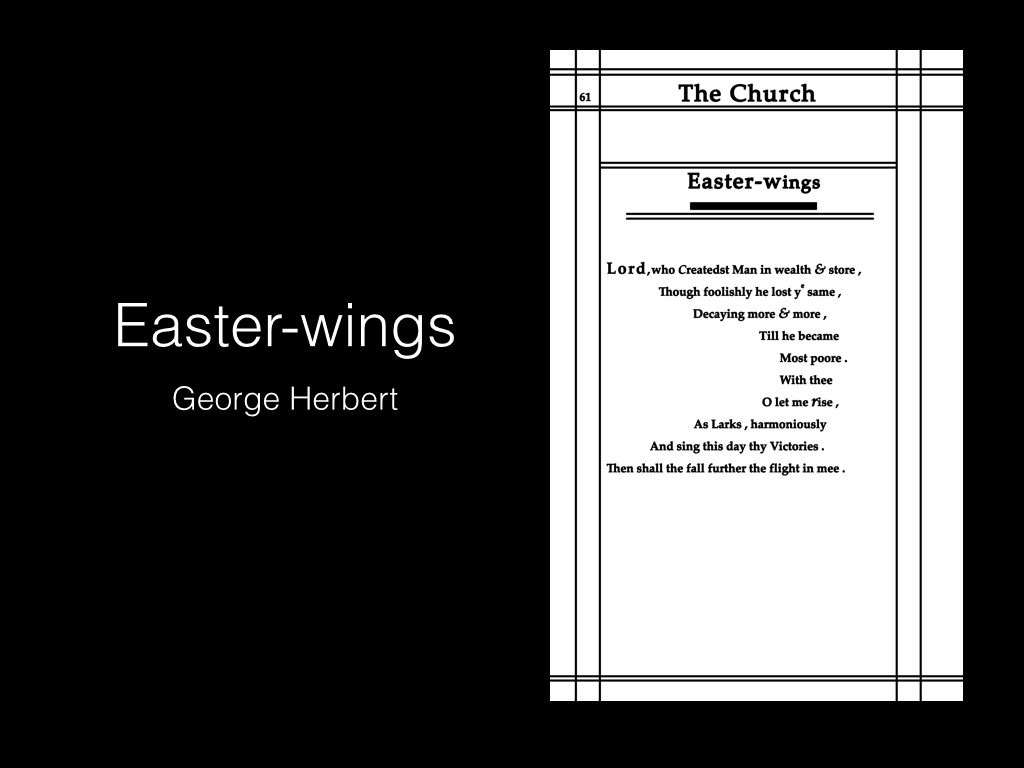

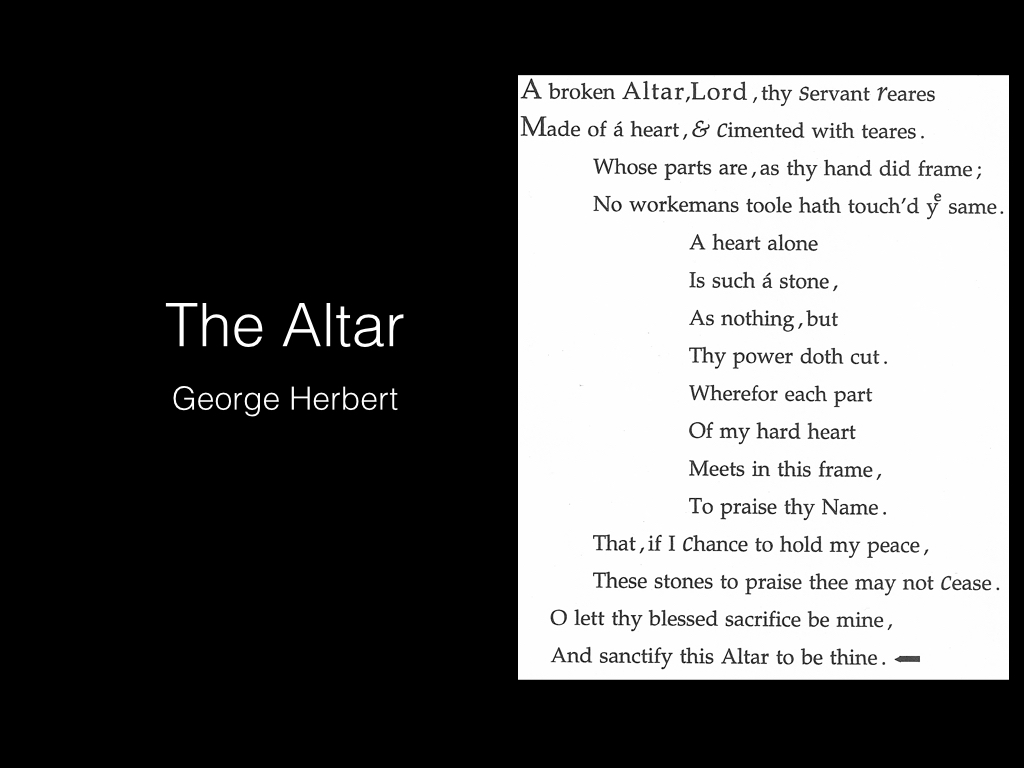

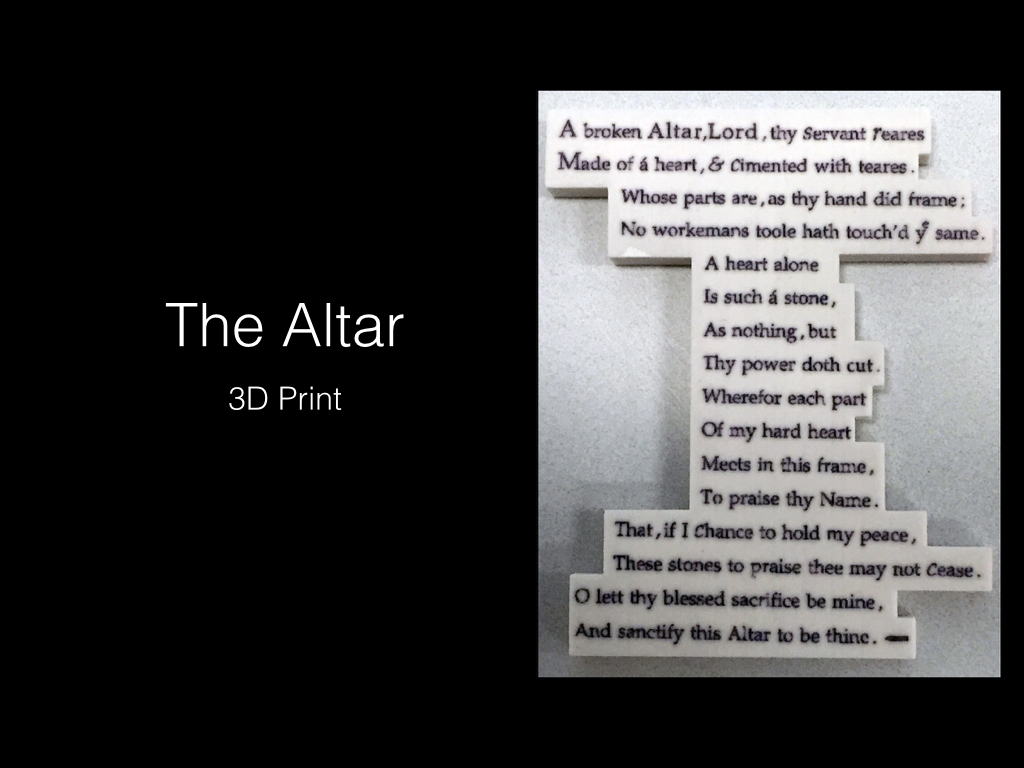

We’ll move now to a discussion of the poems themselves, beginning with George Herbert’s “Easter-Wings” and “The Altar.” These two pattern poems by George Herbert are perhaps the most well known of the genre, and as such, it seemed all but necessary to re-present them as objects. They each presented unique challenges as well as opportunities.

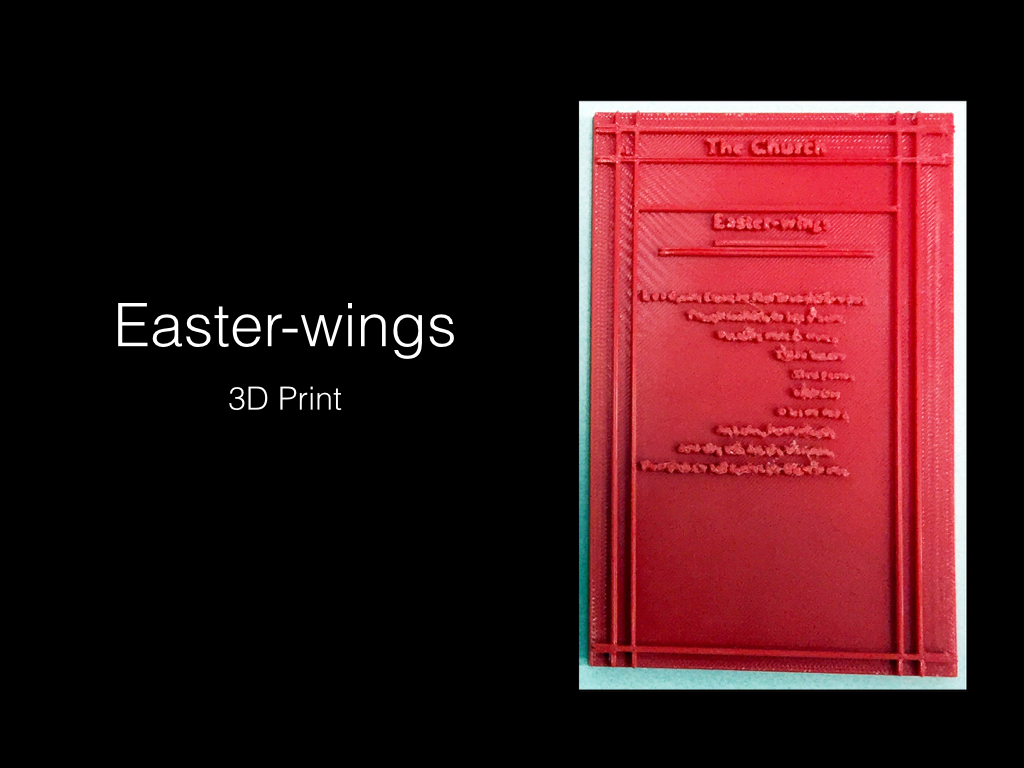

For “Easter Wings,” I chose to use Mario A. Di Cesare’s transcription of the Bodleian manuscript. Di Cesare strongly asserts in his critical introduction that “the two poems named Easter-wings were written as separate individual poems” and “the two were placed horizontally, the indentations of the text pushing lines right-ward (more definitely in W than B). The visual effect is clearly that of birds flying across the sky” (LVIII). This is as opposed to other early renderings of the poem, which take the two poems as one poem with two stanzas, and align the stanzas (poems) vertically.

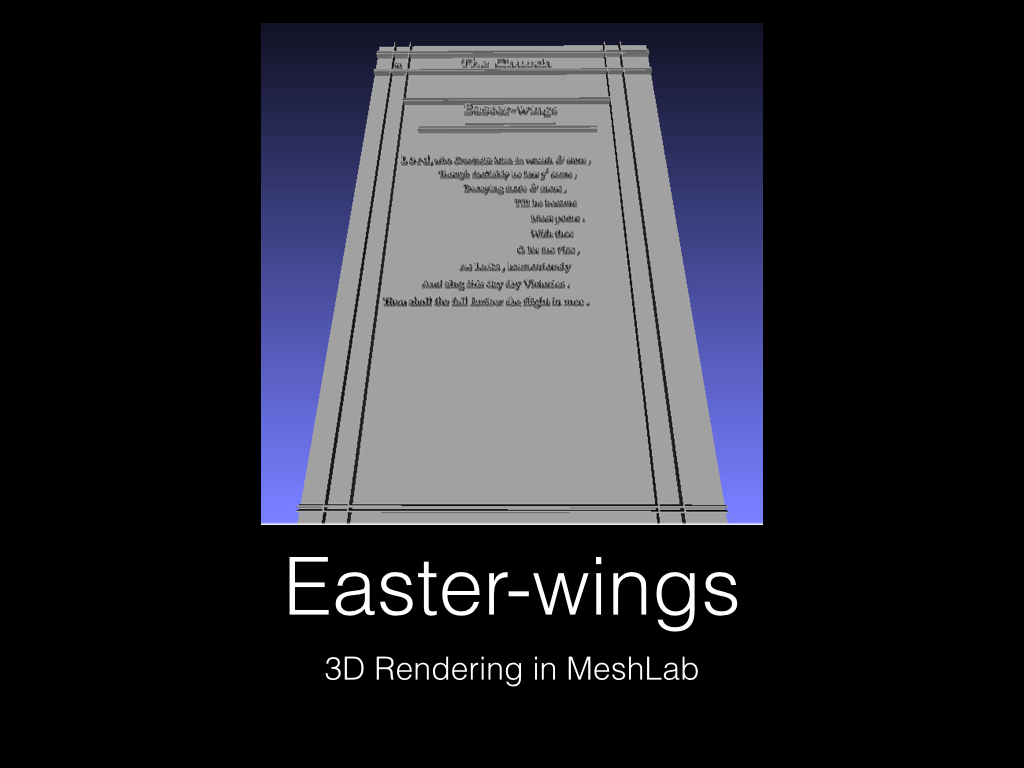

Taking a cue from the seventh line in the poem, “O let me rise,” I decided to attempt making a height map of the poem’s text so that the words would literally rise off of the page. This involved running a computer script called “Image to 3D Printable Heightmap/Lithophane,” created by Amanda Ghassaei, on the image. This script designates a greater height to darker areas of an image and lesser height to lighter areas. The intended effect would be that the text and page border, rendered in black, would rise off the plane of the white page.

I scanned a page of Di Cesare’s transcription and attempted to run the script but found that the resolution of the scanned page was not high enough to create the intended effect. So, to overcome this challenge, I chose to recreate Di Cesare’s transcription using Adobe Photoshop. I used the scan as a base image, over which I retyped the poem’s text, being careful to match the font and spacing as closely to Di Cesare’s as possible, and I redrew the page borders that exist in the Bodelian manuscript as well as Di Cesare’s version.

The object that resulted is not perfect. Apparently, due to its flat and large size, it failed multiple times in the lower cost 3D printer as the base — or the page — would warp and then fail. The piece that resulted is at least structurally sound, but still not perfect. You can get a sense of the original page, but it is not clear enough to read. Also, and for a reason I’m not entirely sure about, the wonderful people at the 3D studio chose to print it on red plastic.

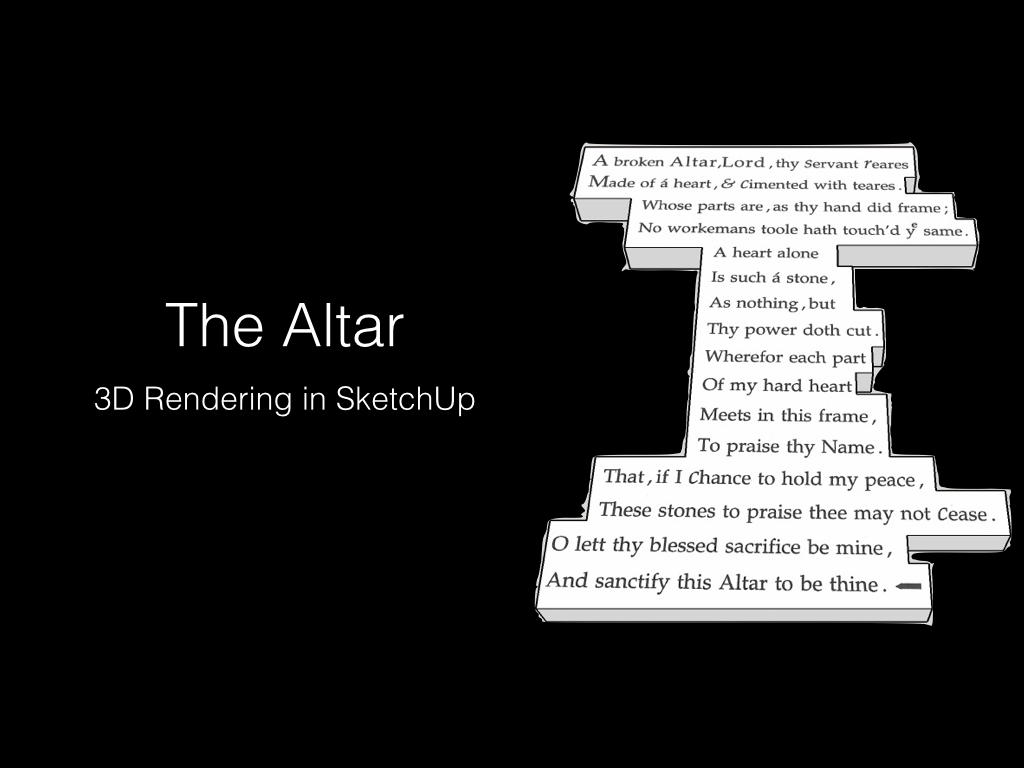

In working with Herbert’s “The Altar,” I chose a much more straightforward approach. Using a scan of Di Cesare’s transcription, I traced the outline of the lines in SketchUp and then used the scanned image as a texture on the surface of the object. My chief concern here was to illustrate the brokenness of the altar as described in the opening line of the poem, “A broken Altar, Lord, the servant reares.” This concern was animated by what I perceive as a misreading by many critics, including Paul Dyck, in his essay “Altar, Heart, Title-Page: The Image of Holy Reading,” in which he writes that “The Altar” has “long had a critical reputation as one of Herbert’s most puzzling poems, precisely because its shape and its words apparently contradict each other: the poem displays a symmetrical, perfected altar while narrating ‘a broken altar’” (541).

And, indeed, in my re-presentation of the poem, again, using Di Cesare’s transcription of the Bodleian manuscript, it is clear that the shape is anything but symmetrical and perfected. Rather, the altar seems to be symmetrical on the left side, but on the right side it is jagged and, in fact, broken. This difference is even more pronounced in the physical object that resulted, which was printed using a kind of powder plaster.

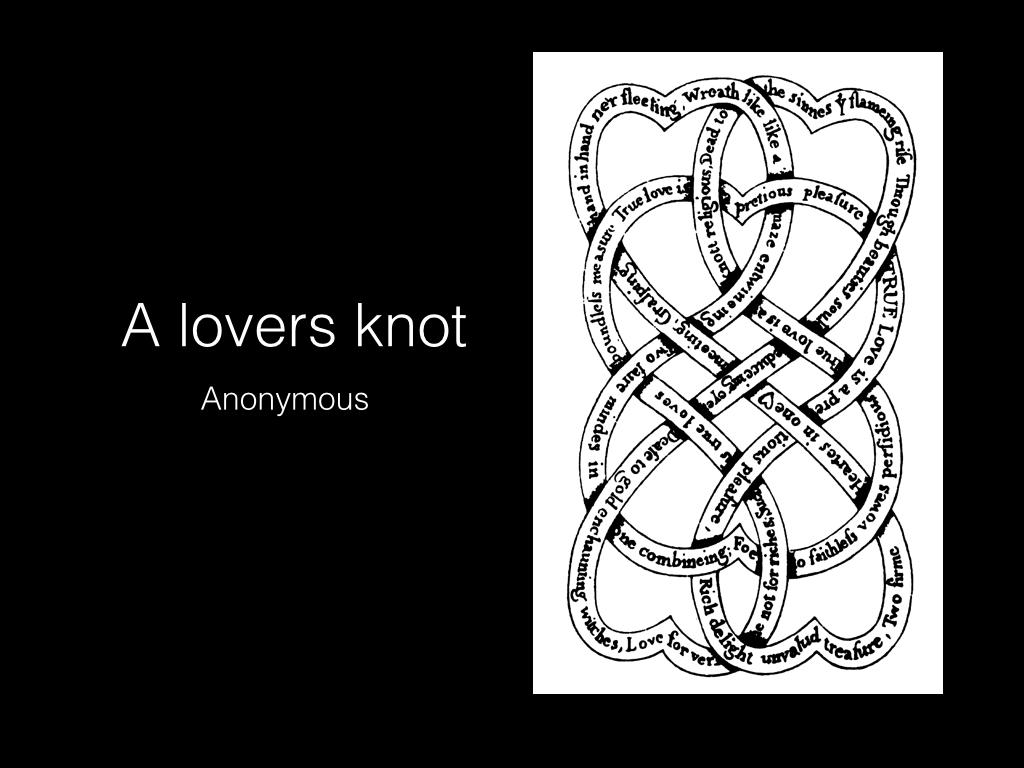

And, finally, we’ll look at the Anonymous true lover’s knot. The idea that prompted this project was first conceived when I encountered the few examples of lover’s knots available in Recreation for ingenious head-peeces, or, A pleasant grove for their wits to walk in of epigrams 700, epitaphs 200, fancies a number, fantasticks abundance, edited by Sir John Mennes and James Smith and published in 1654. I was particularly drawn to the poem that begins (if indeed a beginning can be determined) “TRUE love is a pretious pleasure” because its text and shape so precisely align. Throughout the poem, love is likened to a wreath, a maze that entwines “two faire mindes,” a knot, and two hands grasping. Additionally, the text brings to the reader’s attention the novelty of the shape in noting the “pretious pleasure” of reading such a poem and the way the shape seduces the eye.

Part of the challenge of reading such a poem on the page — and to a much greater extent, reading it in digital facsimile most readily available at EEBO — is the necessity of rotating the page in order to follow the verse. This challenge, combined with my sense that lover’s knots, even more so than other pattern poems, mimic a shape — presumably rope or ribbon tied around itself — prompted me to want to create a version that could be more easily held and rotated to be read.

With the insight and assistance of the staff at Northeastern’s 3D Printing Studio, I decided to use the Studio’s laser cutter to cut the poem into an object, in this case plywood, rather than build it from scratch. This option was available for the lover’s knot due to its more strictly mimetic quality — namely that the text is bordered by lines meant to represent rope or ribbon. The result is a stunning piece that is indeed easier to read and quite pleasurable in the act of rotating and following the thread, so to speak.

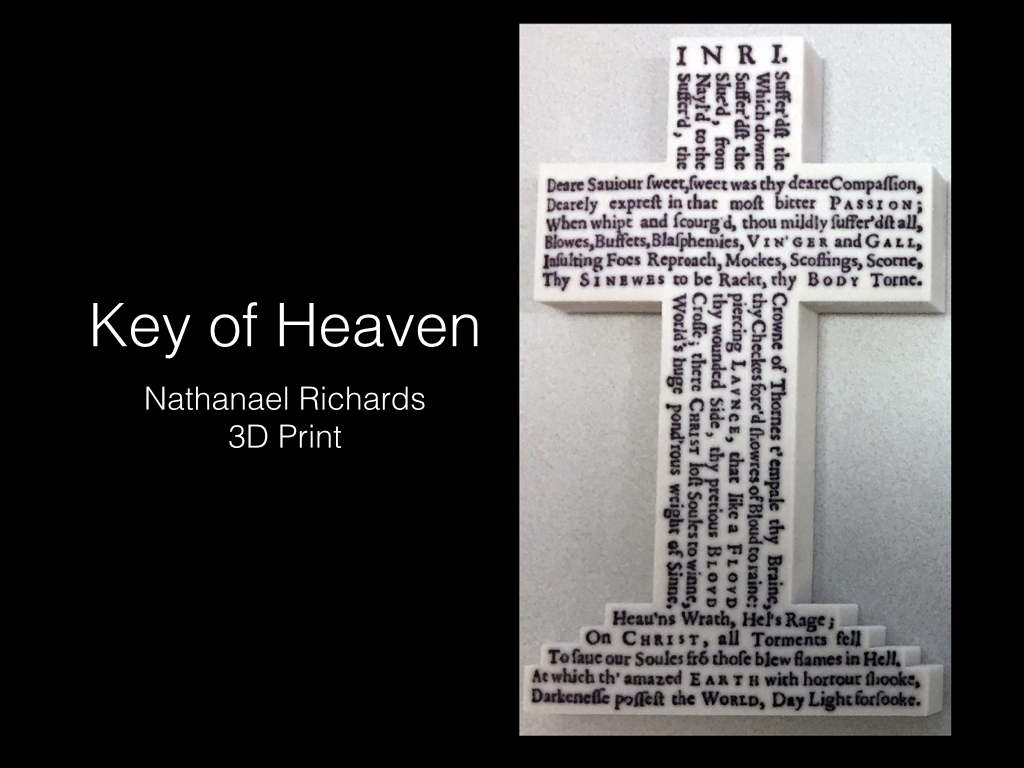

Though I only had the time here to discuss three of the poems I worked with, I did bring the other as well, Nathanael Richards’ “Key of Heaven,” and I’d be happy to share these with anyone who might be interested in getting a closer look.

Conclusion

In her blog post — adapted from a talk she gave at the Geographies of Desire conference in 2012 — Sarah Werner considers “How might we use digital tools to look at texts differently” (Werner). She asks a further question that she then answers with a variety of examples of innovative ways to consider texts, “Can we move away from reading text to studying the physical characteristics of text, characteristics that can reveal important information about the content of the text and the cultural and historical creation of the artifact?” (Werner). Indeed, it is precisely this goal, to better understand the content, as well as the cultural and historical context of Early Modern pattern poetry that incited this project. Through the process of working closely with each poem, in varying instances recreating their texts, outlining their shapes, modeling them in 3D, and finally printing them, I believe we can come closer to understanding their intermedial nature and arrive nearer to that double semiotic that Dick Higgins suggested was key to understanding what he calls, “an unknown literature.”

Works Cited

Brown, C. C., and W. P. Ingoldsby. “George Herbert’s ’Easter-Wings.’” Huntington Library Quarterly 35.2 (1972): 131–142. JSTOR. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

Drucker, Johanna. “Un-Visual and Conceptual.” Open Letter 12.7 (2005): 117. Print.

“Dyck on Herbert’s Shape Poems.pdf.” : n. pag. Print.

Dyck, Paul. “Altar, Heart, Title-Page: The Image of Holy Reading [with Illustrations].” English Literary Renaissance 43.3 (2013): 541–571. Print.

Grusin, Richard A. “Premediation.” Criticism 46.1 (2004): 17–39. Project MUSE. Web. 29 Nov. 2014.

Herbert, George, and Bodleian Library. George Herbert The Temple: A Diplomatic Edition of the Bodleian Manuscript (Tanner 307). Binghamton, N.Y: Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies, 1995. Print. Medieval & Renaissance Texts & Studies v. 54.

Higgins, Dick. “Pattern Poetry as Paradigm.” Poetics Today 10.2 (1989): 401–428. JSTOR. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

---. Pattern Poetry : Guide to an Unknown Literature. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1987. Print.

Liu, Alan. “Imagining the New Media.” A companion to digital literary studies (2007): 1. Print.

McLuhan, Marshall, and Lewis H. Lapham. Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. Reprint edition. Cambridge, Mass: The MIT Press, 1994. Print.

Mennes, John, Sir. Recreation for Ingenious Head-Peeces, Or, A Pleasant Grove for Their Wits to Walk in of Epigrams 700, Epitaphs 200, Fancies a Number, Fantasticks Abundance : With Their Addition, Multiplication, and Division. London : Printed by M. Simmons ..., 1654., 1654. Print. Early English Books, 1641-1700 / 1508:09.

N., J. N. “Visual Poetry.” Poetry 31.6 (1928): 334–338. Print.

Nowviskie, Bethany. “Resistance in the Materials.” Bethany Nowviskie. N.p., 4 Jan. 2013. Web. 14 Nov. 2014.

Puttenham, George. Cornell Paperbacks : Art of English Poesy, A Critical Edition. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell University Press, 2007. ebrary. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

Ray, J.k. “Herbert’s Easter-Wings.” Explicator 49.3 (1991): 140. Print.

Richards, Nathanael, ca. The Celestiall Publican A Sacred Poem: Liuely Describing the Birth, Progresse, Bloudy Passion, and Glorious Resurrection of Our Sauiour. The Spirituall Sea-Fight. The Mischieuous Deceites of the World, the Flesh, the Vicious Courtier. The Iesuite. The Diuell. Seauen Seuerall Poems, with Sundry Epitaphs and Anagrams. By Nathanael Richards Gent. London : Imprinted by Felix Kyngston, for Roger Michell, 1630., 1630. Print. Early English Books, 1475-1640 / 1079:03.

Schreibman, Susan. “Digital Scholarly Editing.” Literary Studies in the Digital Age. Ed. Kenneth M. Price and Ray Siemens. Modern Language Association of America, 2013. CrossRef. Web. 4 Sept. 2014.

Shaffer, E. S., ed. “Technopaigneia, Carmina Figurata and Bilder-Reime: Seventeenth-Century Figured Poetry in Historical Perspective.” Comparative Criticism: Volume 4, The Language of the Arts. Cambridge University Press, 1982. Print.

Skelton, Robin. The Poetic Pattern. London, Routledge and Paul, 1956. Print.

Summers, Joseph H. (Joseph Holmes). George Herbert : His Religion and Art. Binghamton, NY: Center for Medieval and Early Renaissance Studies, 1981. Print.

Werner, Sarah. “Where Material Book Culture Meets Digital Humanities.” Wynken de Worde. N.p., 29 Apr. 2012. Web. 2 Dec. 2014.

West, David. “Easter-Wings. (pattern Poem by George Herbert).” Notes and Queries 39.4 (1992): 448. Print.

Wood, Chauncey. “Paradox and Imping in Herbert’s ’Easter-Wings.’” George Herbert Journal 32.1-2 (2008): 98+. Print.

If you liked this post, consider sharing it or follow me on Twitter.